Introduction to Python 🐍

What is Python?

|

|---|

| Wikipedia’s Definition of Python |

In short:

- Programming language, created in 1991 by Guido van Rossum

- Named after Monty Python

- Used for a wide range of programming, from making web apps to data analysis

Why Python?

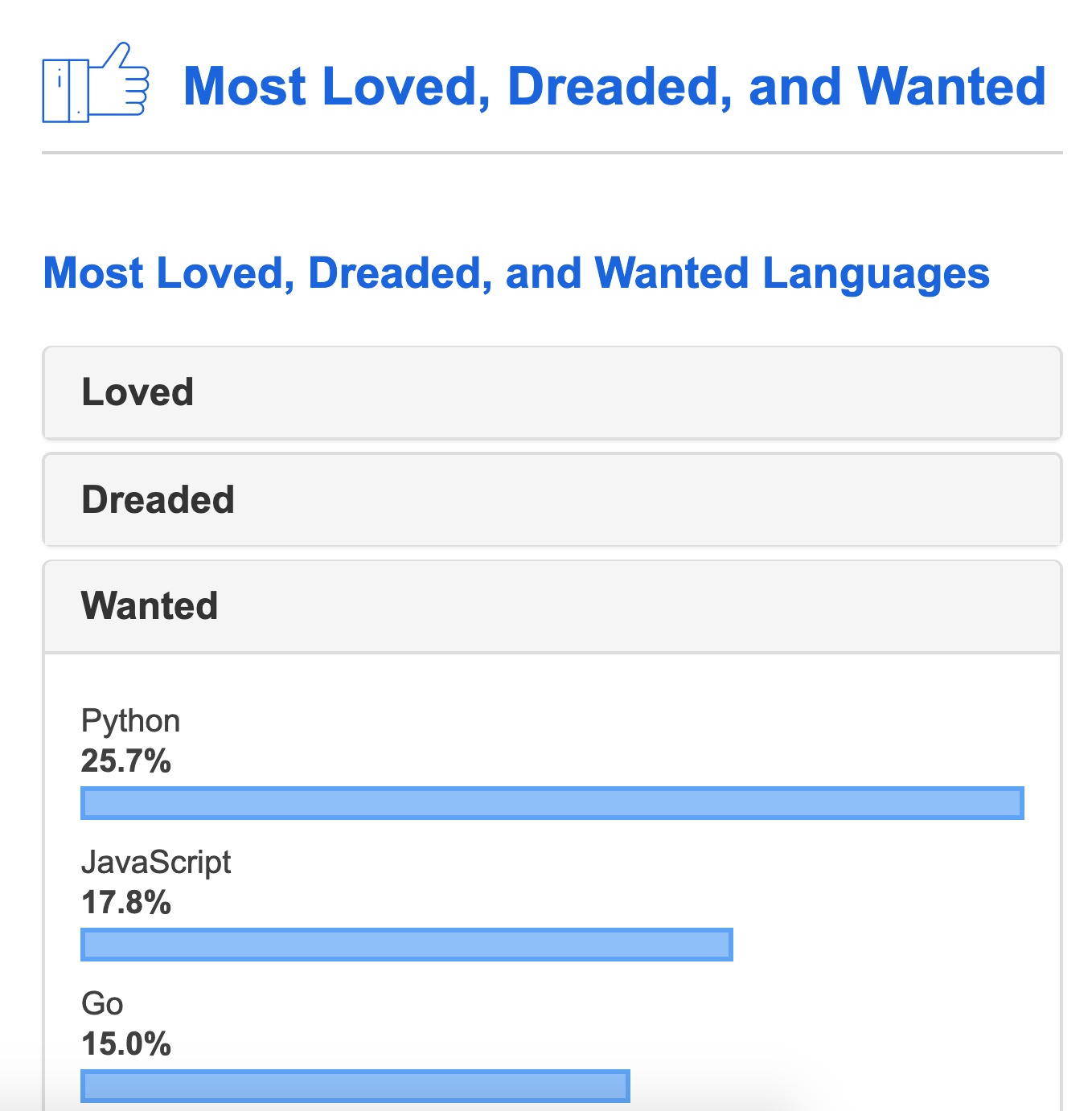

|

|

|---|---|

| Jake VanderPlas Tweet | Stack Overflow’s Annual Survey |

In short:

- Python is well suited to a wide range of programming tasks

- Python has become the standard in a number of industries and academic disciplines

- BUT many of the concepts covered in Python translate to other programming languages too!

Python 2 vs Python 3?

While Python was officially founded in 1991, it only became popular after the release of Python 2.0 in 2000 (not to be confused with Python 2) when the language switched to a more public code repository and a more open, community-driven development model.

Python 3 was released in 2008 as a major reformation of the language that made it more consistent and unified redundant mechanisms. Python 3 is not backwards compatible with Python 2; it is, in effect, a new language. You should definitely use Python 3 because Python 2 is no longer officially supported since January 1, 2020.

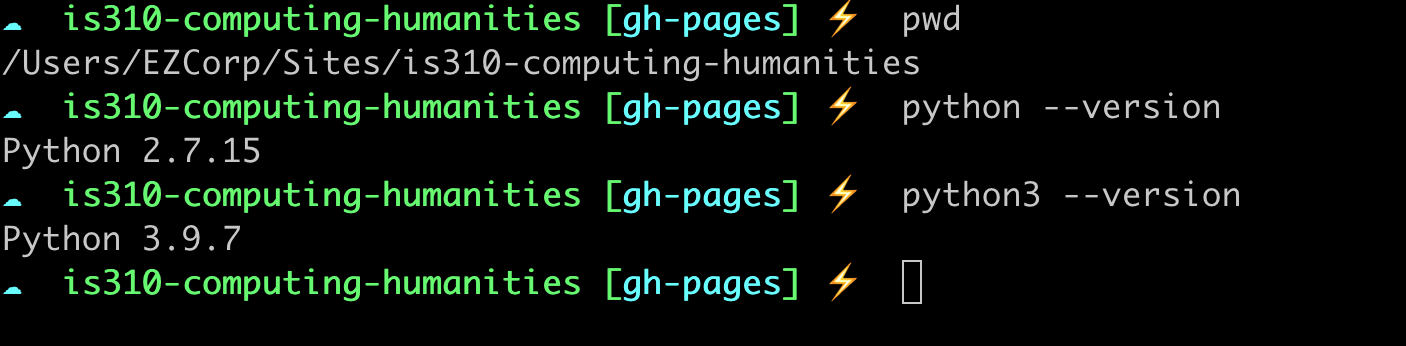

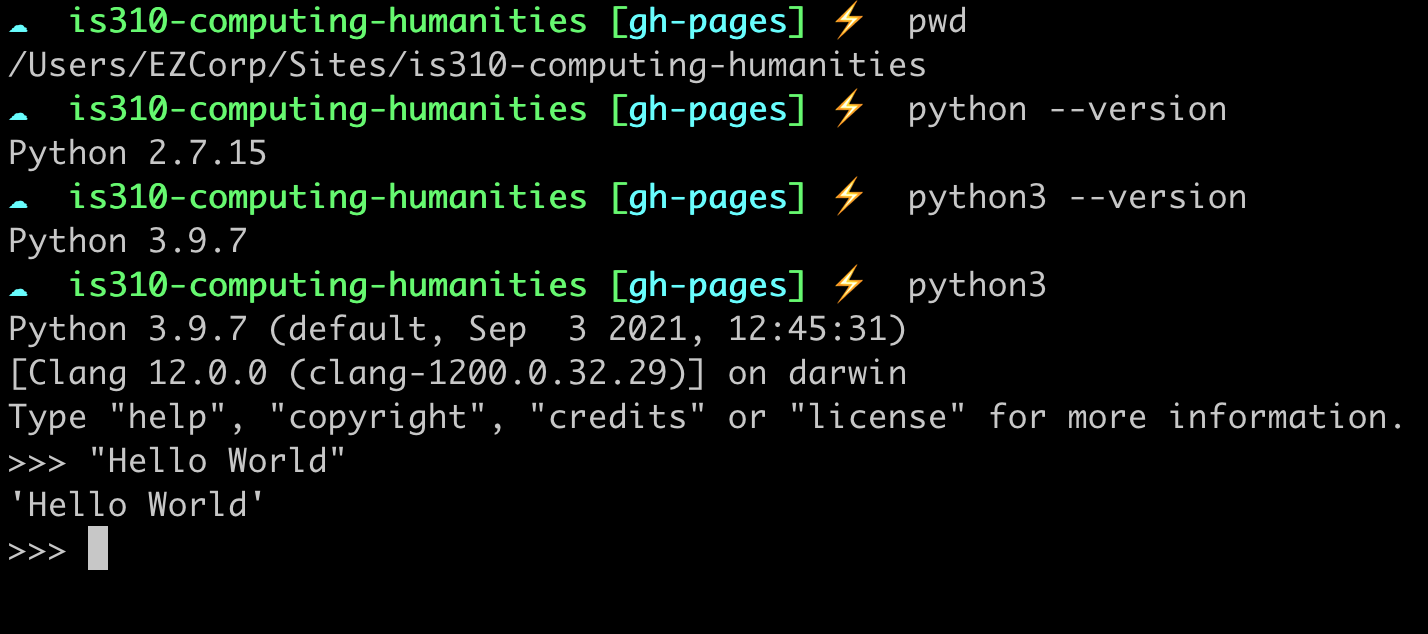

Many computers come with Python 2 already installed by default. Depending on how yours is set up, running python may run the Python 2 or Python 3 interpreter. To determine which one, run the command python --version.

Open your terminal and check your python version

Type:

python --version

python3 --version

You’re results should look something like the following.

If you are getting errors, try looking at the Python Installation Instructions and contact the instructor for help troubleshooting.

Python in the Terminal

In your terminal, type python3. This will open the interactive python interpreter where you can write your python code and have the computer execute it. The python interpreter is an excellent way to sandbox your ideas or check your syntax. You can exit using exit().

- Type

'Hello world'in the interpreter and press enter.

Congrats you’ve just typed your first bit of python and had the computer execute it 🎉!

Let’s breakdown what just happened.

- You entered data into the interpreter.

- That data had a certain format, in this case variable, and the interpreter automatically showed that data again.

We can also use the interpreter as a calculator. Try out these examples.

1+1

2**3

You’ll notice that though the interpreter prints out when you press enter, the results of our calculations aren’t saved any where. What if we wanted to save our data?

Python Variables

We can save our hello world data into a variable and keep using it again and again.

var = 'Hello world'

Now try typing var again. What happens?

The var variable now has ‘Hello world’ stored inside. Python understands that our variable contains a string. You can type any string and store it into a variable.

one = 'one'

two = 'two'

three = 'three'

Python knows that these variables contain strings because of the use of either single(‘’) or double quotes(“”).

Python Data Types

Strings are just one of many data types accepted in Python.

There’s also numbers, called integers. We can take our variables that we assigned before and assign them their actual numbers.

one = 1

two = 2

Once we do this though, our strings that were stored in these variables will be erased!

What happens if you try and use a number for your variable?

1 = 1

You’ll get a syntax error! That’s because Python has rules for how to name variables.

- A variable can have a short name (like

xandy) or a more descriptive name (age,carname,total_volume) - A variable name must start with a letter or the underscore character

- A variable name cannot start with a number

- A variable name can only contain alpha-numeric characters and underscores (A-z, 0-9, and _ )

- Variable names are case-sensitive (age, Age and AGE are three different variables)

So what makes a good variable name?

As a general rule of thumb, I would recommend choosing names that are short and descriptive. In Python, we also tend to use underscores for naming (versus Javascript where you use camelCase). For some more examples, see Melanie Walsh’s note on “Striving for Good Variable Names”.

So our previous example could work if we changed the variable name to:

one_1 = 1

Python also has a special name for floating point numbers, called floats.

one = 1.0

Integers are simple and easy to use. Floats are mostly easy, but sometimes really weird!

Weird Numbers

What does this return?

0.1+0.2

Huh, weird.

All data in a computer is represented as binary (base 2) numbers, comprising only 1s and 0s. The text you’re reading now is represented by individual characters that, under the hood, are stored as binary numbers. The method of translating these information between different forms and contexts (such as between binary numbers and text or numbers) is called encoding.

Integers are easy enough to represent in binary: 0 is 0, 1 is 1, 2 is 10, 3 is 11, 4 is 100, and so on.

But floats are trickier and require a special system to represent. Don’t worry about it for now, but consider for a moment that it’s impossible to represent exactly 1/3 in finite decimal notation (0.3333…). It’s similarly impossible to represent some simple decimal numbers in a binary notation. Which is why you get the weird results above.

For more information check out Float to Binary Converter and IEEE 754 Standard.

Python Methods

What if we decided that we wanted to combine variable one and two? We could use a built-in Python method for manipulating variables and data.

- To join variables together use the

+symbol, this is called concatenation.

one + two

You should see 3.0 as your answer. We just added the data in variable one and two together.

What would happen if we added variables var and three together?

var + three

Python strings are “immutable” which means they cannot be changed after they are created (Java strings also use this immutable style). Since strings can’t be changed, we construct new strings as we go to represent computed values. So in this example we concatenate var and three, which builds a new string ‘Hello Worldthree’.

Other methods that you can use on integers and floats:

- division:

one / two

- multiplication:

one * two

- We can also assign a truth value to a variable, called a boolean.

var_true = True

var_false = False

We can then check if these two variables contain the same truth value.

var_true == var_false

In Python = is used to assign values to a variable, and == is used to check if two variables contain the same value. True in Python is interchangeable with the number 1 and False with 0.

Quick Assignment

In your Python interpreter complete the following prompts:

- Google two tools listed in our reading from this week “Which Dh Tools Are Actually Used In Research?”.

- Assign to variables their names and the year they were first released.

- Try testing if their names are equal or if they were released in the same year.

- Try joining their names together.

- Try adding/multiply/dividing their release years.

Python Data Structures

Typing the information of two or three DH tools is doable, but what if we wanted to do every single one listed in the article? Typing a new variable each time to assign their value is really tedious!

That’s where data structures come in! In Python, we can store data types in various data structures that are optimized for different problems.

Lists

If we wanted to take the names of every tool in the article, we could store them in a data structure called a list.

tools = ['Twitter', 'Gephi', 'HathiTrust']

A list is an unordered, comma-separated collection of any values. So we can store any combination of values in our list.

tools = ['Twitter', 'Gephi', 'HathiTrust', 2019]

We can also store a list inside of another list.

tools = ['Twitter', 'Gephi', 'HathiTrust', 2019, ['MALLET']]

What if you want to just print out ‘Twitter’ from the list? We can do that by indexing the list.

tools[0]

Each list in Python is a sequence, and we can access the position of an item in that sequence through indexing. In Python, indexes always start at zero!

We can use indexing in all sorts of ways.

- We can take the final item by using negative one, which tells Python to get the last item from the list

tools[-1]

- We can take a range of items by using a colon to specify when we want to start and stop

tools[1:3]

- If we try to index longer than the list, we’ll get an error that tells us we’re out of range of the list

tools[8]

Now what if we wanted to add DH projects to our list? We could create a new list that contained the projects and then use concatenation to join them.

projects = ['Prof Gender', 'Ngram Viewer']

tools + projects

We can see in the interpreter that we now have a list containing both lists, but what happens if you type tools again?

Remember to store values, we need to assign them to variables.

projects = ['Prof Gender', 'Ngram Viewer']

new_list = tools + projects

We can also add items and remove them from the list. Let’s take a look at some of these methods https://www.w3schools.com/python/python_ref_list.asp. You can read more about them in the python documentation https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/datastructures.html and in Melanie Walsh’s textbook https://melaniewalsh.github.io/Intro-Cultural-Analytics/02-Python/06-String-Methods.html#id1.

Quick Assignment

Try out the methods in the documentation for manipulating lists

- Find a way to add ‘SlaveVoyages’ to the end of our

new_list(hint: there’s multiple ways to do this) - Try reversing and sorting our

new_list, what happens? Try doing the same onprojects

Lists are great. But what if we wanted to store information not just in a sequence, but in a way that let’s us keep certain values together?

Dictionaries

We can use a dictionary, which is a collection of key/value pairs to store this information. Keys and values are always separated by a colon.

tool = { 'name': 'Gephi', 'founded_year': 2008}

To access our values in dictionaries, we don’t use indexing. Instead, we use the keys of dictionary. Keys are always the values that come before the colon.

tool['name']

We write the key inside of brackets and quotations, called bracket notation.

What happens if we add another tool to the dictionary?

tool = { 'name': 'Gephi', 'founded_year': 2008, 'name': 'HathiTrust'}

Where’s Gephi??

Gephi was overwritten in our dictionary because our new value shared the same key. In a dictionary, keys must be unique!

Just like lists though we can store a dictionary inside of a dictionary

tools = {

'tool_1': {

'name':'HathiTrust'

},

'tool_2': {

'name': 'Gephi',

'founded_year': 2008

},

}

Now we can get Gephi’s name if we type tools['tool_2']['name']. What’s happening here is that we’re using the keys to find our value that’s nested inside a dictionary within a dictionary.

We can add Gephi’s release year by using a similar notation:

tools['tool_2']['founded_year'] = 2008

Just like lists there are many ways to manipulate dictionaries https://www.w3schools.com/python/python_ref_dictionary.asp

Quick Assignment

Try out the methods for manipulating dictionaries.

- Remove Gephi’s founding year from the

tool_2dictionary - Get all the keys for the

toolsdictionary - Get all the values for the

tool_1dictionary

You can also get even crazier and store lists in dictionaries:

tools = {

'tool_1': {

'name':'HathiTrust',

'projects': ['Bookworm', 'Google Ngram Viewer']

},

'tool_2': {

'name': 'Gephi',

'founded_year': 2008

},

}

Notice that the list is a value of a key, in this case projects. You can only insert a list into a dictionary as a value.

You can also put dictionaries inside of lists:

tools = [

{

'name':'HathiTrust',

'projects': ['Bookworm', 'Google Ngram Viewer']

},{

'name': 'Gephi',

'founded_year': 2008

}

]

Notice that we now don’t have keys for our top-most dictionaries. In lists, items don’t have keys, so each of your dictionaries is without an explicit key.

Python defaults to indexing each dictionary with numbers, just like in our list of strings. So to get the first value, you would type:

tools[0]

Congratulations 🎉🎉🎉! You’ve now completed the introduction to Python.

If anything is unclear, please bring questions you have to class or the instructor, and we will be doing an overview of these concepts. Also checkout the Python Cheatsheet!

Now that you have completed introduction to Python, move on to Python Fundamentals here.