Introduction to Named Entity Recognition

Download relevant libraries

Before we start today, I want to get people downloading the relevant libraries for this lesson since they are a bit larger than our previous Python packages. If you are using a virtual environment, be sure to activate yours before downloading the libraries.

source is310-venv/bin/activate

pip install spacy

python3 -m spacy download en_core_web_sm

We’ll jump into this later on but let me know if you have any error messages when running these commands.

Previously talked about information retrieval versus information extraction in regards to unstructured, textual data. While we explored information retrieval in the context of TF-IDF, we will now explore information extraction with Named Entity Recognition.

What is Named Entity Recognition?

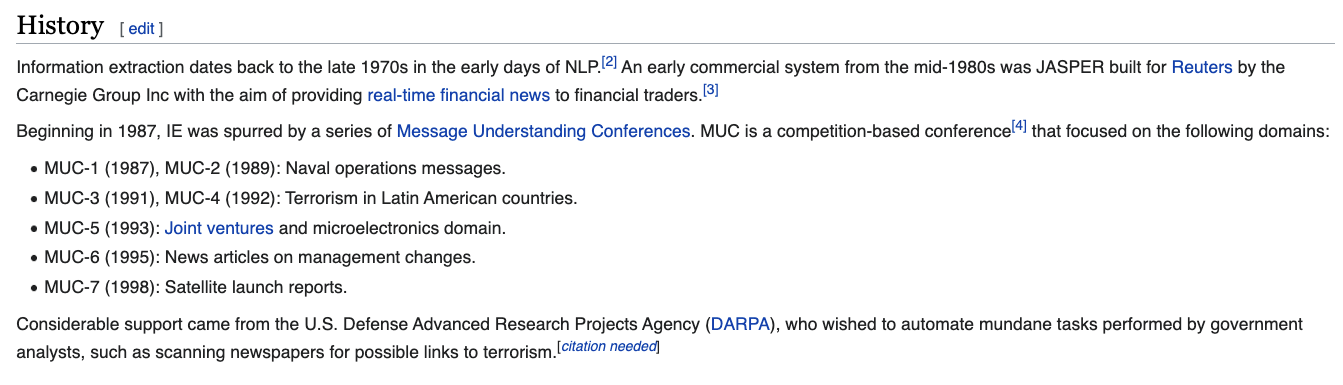

From the Wikipedia article:

“Named-entity recognition (NER) (also known as (named) entity identification, entity chunking, and entity extraction) is a subtask of information extraction that seeks to locate and classify named entities mentioned in unstructured text into pre-defined categories such as person names, organizations, locations, medical codes, time expressions, quantities, monetary values, percentages, etc.”

What does this look like in practice? Let’s look at a few examples.

We can see that in these images, parts of the text are being highlighted and classified as different categories (or entities if you will). Many of these examples might seem straightfoward, but how do we decide what is an entity exactly? And how did NER become a defined field instead of just being part of text mining?

This graph represents a common typology of NLP tasks, comparing it to Natural Language Understanding and Automatic Speech Recognition.

While technically correct, I find this graph confusing 🤔. The exact definition of NER’s boundaries relative to other nlp/nlu tasks is very porous. For example, in addition to recognizing entities, NER can also include parts of text classification, entity disambiguation, relationship extraction all parts of NER (though they are separated in this chart).

So if this is so porous how did NER first develop?

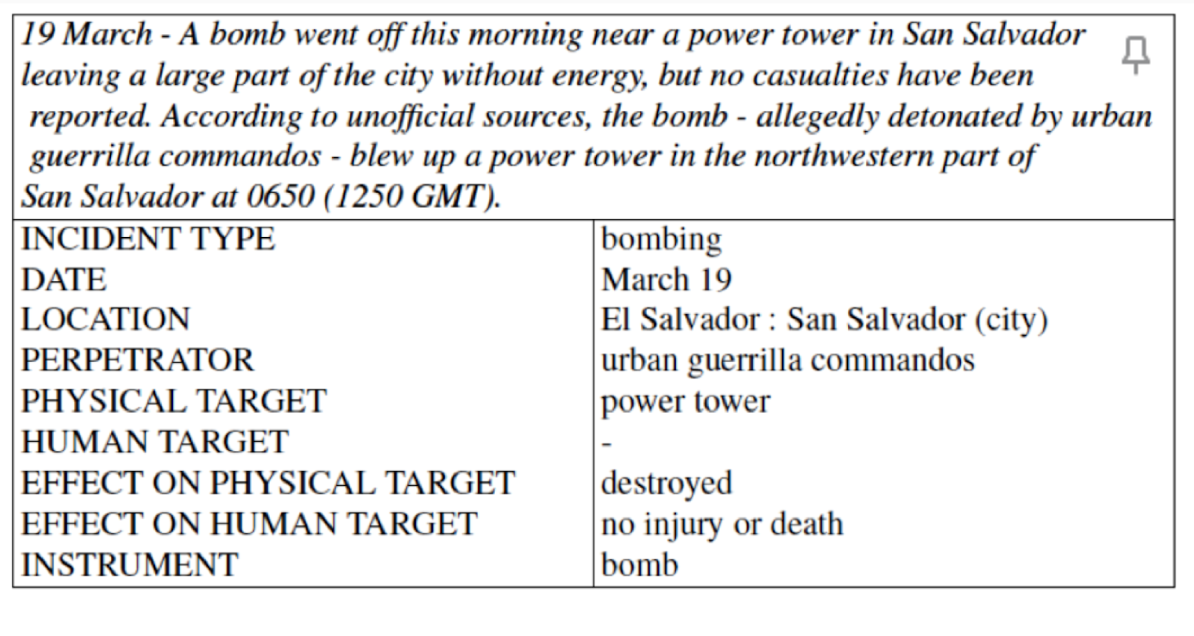

From this Wiki page, we can see that the concept of “named entity” first developed at the Message Understanding Conference-6 in 1995. Here’s an example template given to participants from MUC-3 and you can even read the original MUC manual here https://www-nlpir.nist.gov/related_projects/muc/muc_sw/muc_sw_manual.html:

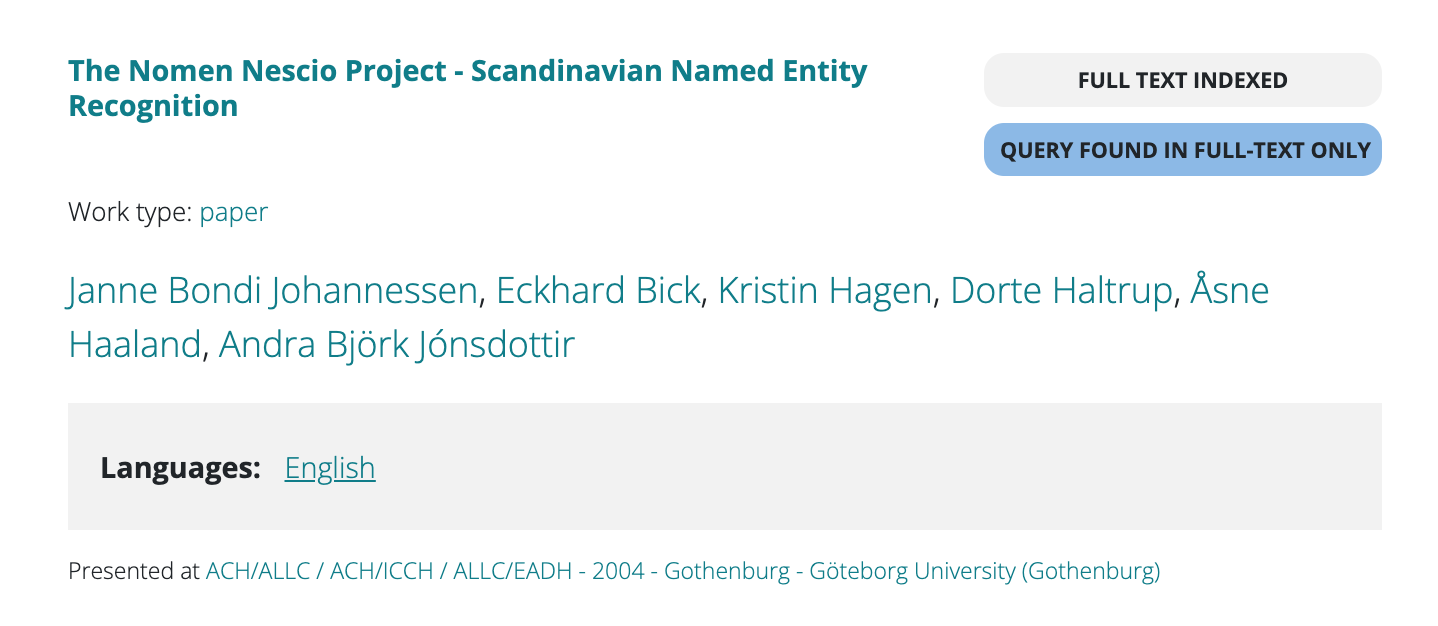

Big takeaway is that NER is relatively new. The field really takes off as a field with Text Analysis Conferences beginning in 2009 https://tac.nist.gov/ and it is also relatively recent in digital humanities.

The first DH conference presentation listing NER as a topic was in 2004:

We’ve also read Skallerup Bessette, Lee and Quinn Dombrowski. “DSC Multilingual Mystery 2: Beware, Lee and Quinn!”. February 27, 2020. https://datasittersclub.github.io/site/dscm2.html where we’ve seen an example of using NER. Did everyone get a sense of this reading? What about the use of NER?

Class erupts into rapid discussion

NER and Python

So now that we have discussed the reading above, let’s try out some NER with some Python. So far we’ve actually used a Python library that is very popular for NER, NLTK. You can read more on using NLTK for this task here https://www.nltk.org/book/ch07.html but today we will be using a different library called spaCy https://spacy.io/ (the same library used in the DataSitters article).

While we have been primarily using our humanist listserv dataset, today we will be returning to our Pudding Film Dialogue dataset. To help with this exercise, I have created a cleaned up version of the Pudding’s public dataset that you can download here.

Once you have that downloaded, let’s create a new Jupyter notebook called IntroNER and load in this dataset.

#Which libraries do we think we might need?

#What datasets should we load in? And what should we name our variables?

Now that we presumably have our dataset loaded, let’s try to do some NER. First we will need to load in the spaCy library.

import spacy

nlp = spacy.load('en_core_web_sm')

# Or use the default model, which has fewer features:

# nlp = spacy.load('en')

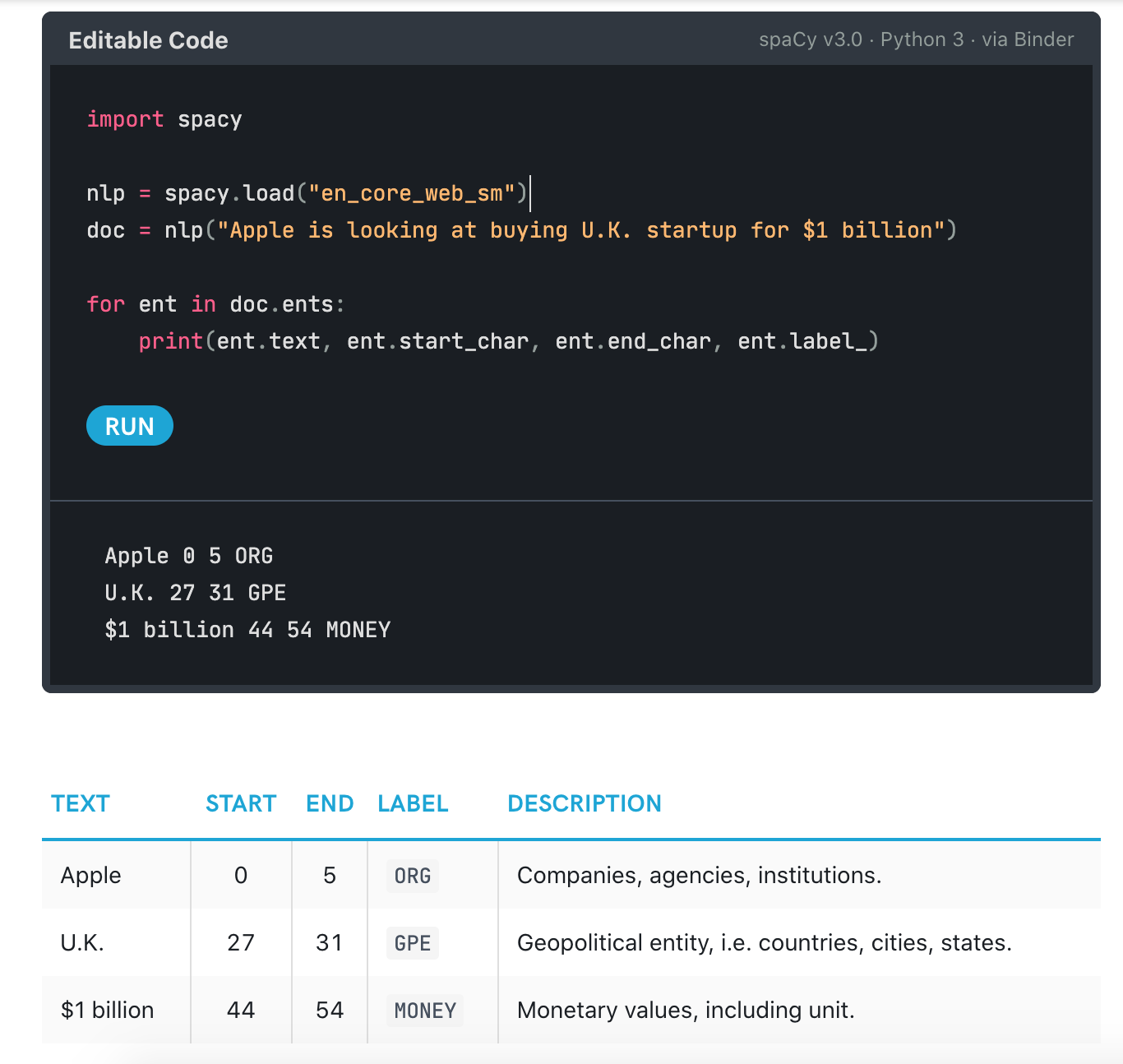

Now spaCy is a much more complex library than we have used before so let’s try out an example and then talk through some the documentation. Let’s start with an example from their spaCy 101 guide https://spacy.io/usage/spacy-101#annotations-ner and try copying some code.

doc = nlp("Apple is looking at buying U.K. startup for $1 billion")

for ent in doc.ents:

print(ent.text, ent.start_char, ent.end_char, ent.label_)

We should see the following output:

So what exactly does this output mean? Well first let’s explore a bit of the spaCy API. First how could we check out what our doc variable contains?

We should see spacy.tokens.doc.Doc so let’s take a look at the Doc https://spacy.io/api/doc. The documentation is pretty dense, but we should get a sense that a Doc is a collection of Token classes, and that it has a number of built-in methods.

We can list these methods with the following code:

# Let's dig into what this Class gives us

[prop for prop in dir(doc) if not prop.startswith('_')]

first_word = doc[0]

type(first_word)

[prop for prop in dir(first_word) if not prop.startswith('__')]

Take a look at the similiarity and ents methods. What do these methods/attributes do?

Part of understanding what they are doing, requires understanding how spaCy works. Below is a figure of their pipeline:

This gives us a bit of a sense of how this is working (recognize tokenizer?) but let’s also read their broad overview page https://spacy.io/usage/facts-figures.

Looking at their comparison usage, what do you think are the benefits and limitations of spaCy? How does spaCy create their models and what are these models exactly?

Returning our example above, let’s try using one of spaCy’s built-in visualizations to understand how this is working.

from spacy import displacy

displacy.render(doc, style="dep")

We should now see something that looks like this:

What this visualization is highlighting is essentially how spaCy works, which is with something called Parts of Speech Tagging.

From the spaCy docs:

After tokenization, spaCy can parse and tag a given Doc. This is where the trained pipeline and its statistical models come in, which enable spaCy to make predictions of which tag or label most likely applies in this context. A trained component includes binary data that is produced by showing a system enough examples for it to make predictions that generalize across the language – for example, a word following “the” in English is most likely a noun.

So the key thing to understand is that this super powerful library also comes with a lot of built-in assumptions about how language in your corpus is structured.

Now that we’ve considered some of the pros and cons, let’s try out spaCy’s NER with some of our film dialogue. Let’s pick one of our titles and try and passing it to spaCy.

# How could we select just one of our film titles?

# How could we create a new spaCy Doc from this?

Now let’s try and take a look at some of our entities. You’ll notice previously that in our example there was a number of different entities highlighted. Below we can see the number of entities that exist in spaCy. Let’s try and print out just one type of entity initially.

# How could we loop through our entities?

# How could we print out just one of the entities?

Now let’s try out visualizing our entities with the spaCy entity visualizer https://spacy.io/usage/visualizers.

# How could we visualize our entities?

# Do we need to shorten our script to visualize everything?

In Class Exercise

- Try taking our existing code and rewriting it into a

applyfunction that takes a row and a type of entity and returns a list of entities into a new column into ourfilm_scriptsdataframe.

Advanced NER

So far we have been letting spaCy do all the work for us in terms of identifying entities. But with our film dialogue dataset we actually have some already identified - specifically, the character entities. Let’s try and merge our film_scripts dataframe with these other csv files.

#Which files do we need?

#How could we merge these files?

Let’s compare the character names with the PERSON entities that spaCy has identified.

#How could we compare these entities? What should we print out?

Looking at these results how useful do you think spaCy is for identifying characters? What might be some of the limitations of this approach?

Rules-Based NER and Gazetteers

So far spaCy has identified some characters compared to what we have from The Pudding which might be useful depending on our goals, but might also introduce a lot of noise.

One way to think of our characters metadata is as a gazetteer.

Gazetteers are a popular method in DH of dealing with variation in NER and identifying historical entities. You can look at the World Historical Gazetteer as an example http://whgazetteer.org/.

With our characters list as a gazetteer, we could just keep trying to write more and more complex for loops, but alternatively we could join spaCy with this gazetteer by adding in new rules to our model.

#Create the EntityRuler

ruler = nlp.add_pipe("entity_ruler")

patterns = [

{"label": "PERSON", "pattern": "CHARACTER_NAME"}

]

ruler.add_patterns(patterns)

doc = nlp(#what is the text we want to analyze?)

#extract entities

for ent in doc.ents:

print (ent.text, ent.label_)

We can read more about rules based NER in William Mattingly’s textbook http://ner.pythonhumanities.com/02_rules_based_ner.html and the spaCy documentation https://spacy.io/api/entityruler but we will go into more depth on Thursday. For now let’s try together to add in our remaining characters and see if we can improve Spacy’s functionality for our goals.

In Class Exercise

- First, try and and train our model with all the characters from our scripts. How could you replicate that patterns code from above but add in more characters?

- Second, building from our initial

applymethod, try rerunning this code with thePERSONentity and saving it to a new column to see if you can get more results. - Bonus, try and visualize these results using altair. You might consider what you would count (maybe unique characters appearing in a film) and also what trends might be most interesting.