Introduction to The Web

We all use the web constantly, but what exactly is it?

Turning to our reliable source of information, Wikipedia, we find the following definition:

“The World Wide Web (WWW), commonly known as the Web, is an information system where documents and other web resources are identified by Uniform Resource Locators (URLs, such as https://www.example.com/), which may be interlinked by hypertext, and are accessible over the Internet.[1][2] The resources of the WWW are transferred via the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) and may be accessed by users by a software application called a web browser and are published by a software application called a web server.”

While this is technically a definition, there’s a lot to unpack here.

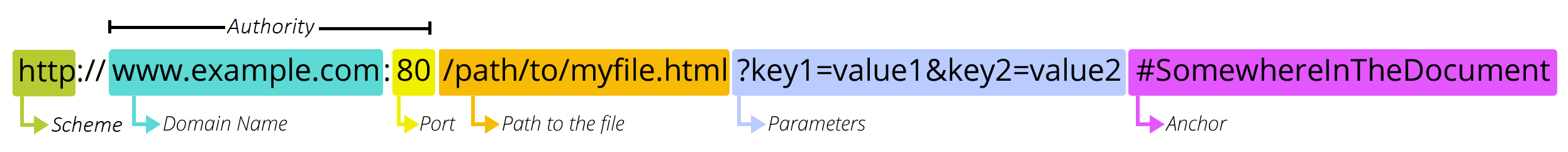

What are Uniform Resource Locators (or URL)?

This diagram is from the Mozilla Web Docs, which provide a great overview of the topic https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Learn/Common_questions/Web_mechanics/What_is_a_URL. You’ve already encountered URLs when we created an a tag in our HTML page.

<a href="https://www.google.com/">Google</a>

This is a type of Hyperlink or Link that allows us to link to other webpages. In our case, we created something called an external link because we linked to a webpage that is not part of our website. But you can also create internal links that link to other pages on your website, or anchors that link to specific parts of a webpage (this is how the sidebar to navigate this page functions). You can read more about hyperlinks here https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Learn/Common_questions/Web_mechanics/What_are_hyperlinks.

But URLs are more than just links; they are the way we access webpages. Mozilla describes URLs as akin to postal addresses, an analogy I find helpful. Just as you need an address to send a letter, you need a URL to send a request to a webpage. Before delving into the anatomy of URLs, understanding domain names and the web’s functionality is beneficial.

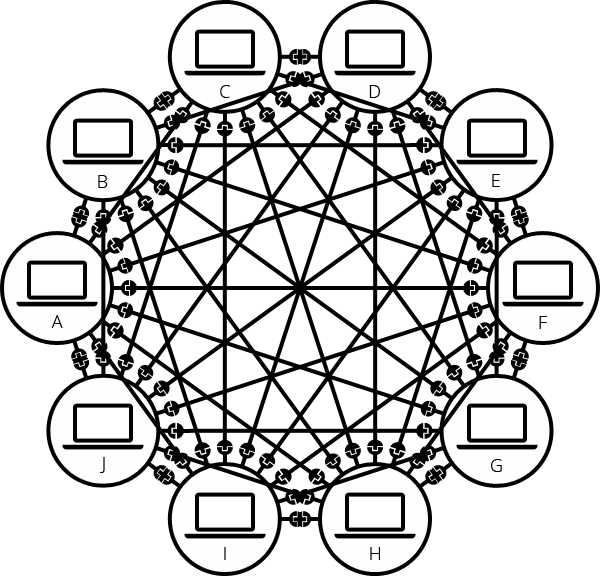

While we often talk about the cloud, the concept of the web was originally based on the idea of a web of interconnected computers.

While this is a simplified explanation, essentially each computer operates as both a client and a server. A client is a computer that requests data from a server, and a server is a computer that provides data to a client in response.

Although our current internet is vastly more complex, this core idea of a client requesting data and a server hosting and sending data remains central to how the web functions. For those interested in a more detailed history of the internet, I highly recommend this timeline from the Computer History Museum, covering developments from the 1960s to the 1990s https://www.computerhistory.org/internethistory/ and also happy to recommend additional readings.

Much of the data sent from servers to clients consists of HTML documents, but it can also include images, videos, audio, or virtually any type of data.

So, besides understanding that we have clients and servers, the other core concept is understanding how these computers communicate with each other, using something called the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP).

What is HTTP?

You’ll notice that almost every URL starts with http:// or https://. This indicates the the protocol used by the client and server use to communicate with each other. This standard was developed in the early days of the web, and allows for the client and server to understand each other.

I particularly like Julia Evans’ Zine on HTTP for explaining this concept:

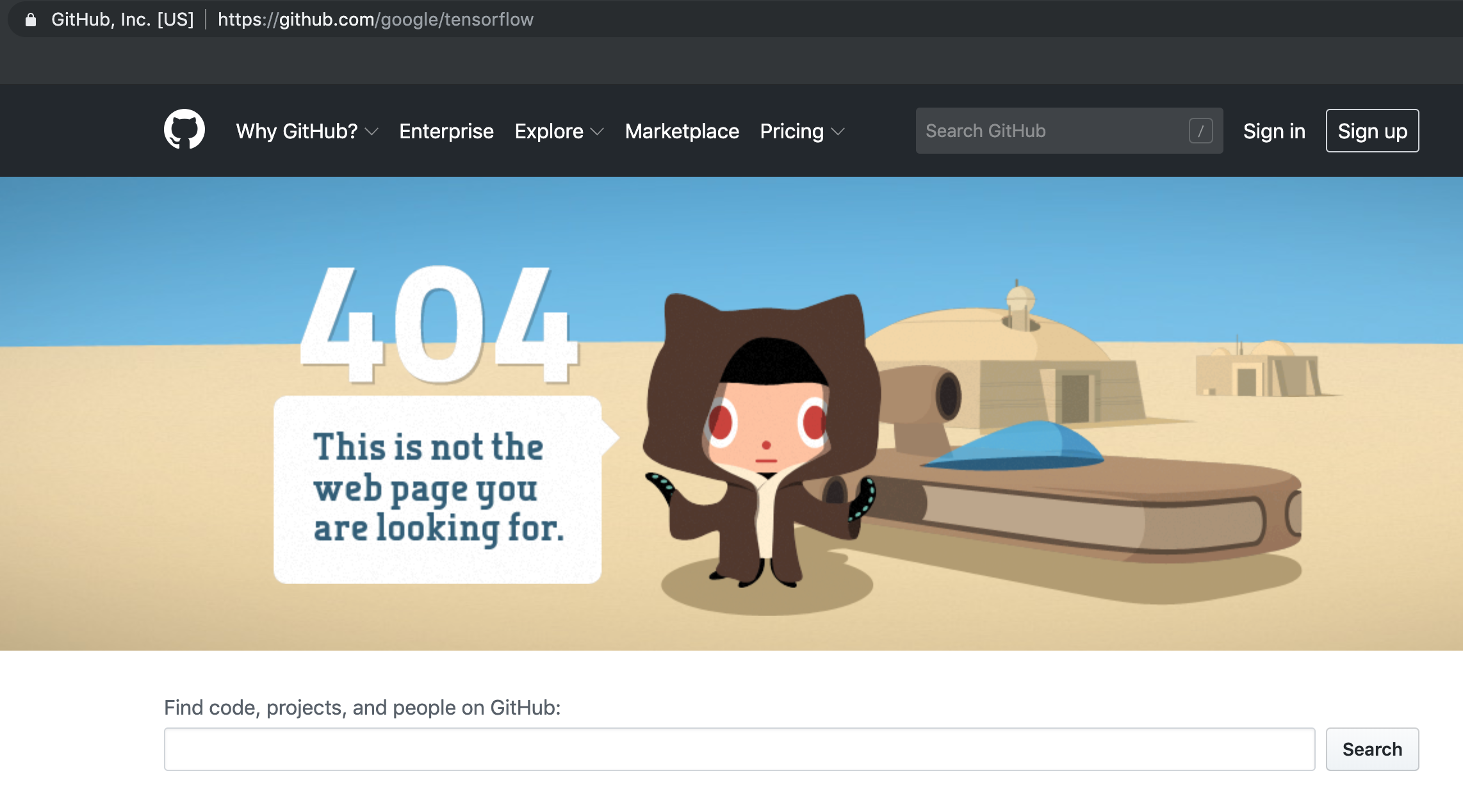

This might seem technical, but the core idea is that when we enter a URL for a webpage (like google.com) into a web browser (like Chrome), we’re actually sending an HTTP request to a server that hosts the HTML files and data. If the server validates our request (with a 200 OK status), it grants access to the webpage.

There’s a number of different types of status codes, that you can see here:

But the most important are either 200 which means the request was successful, or 404 which means the request was not successful.

So, if you’ve ever seen an error message when you go to a webpage saying the page doesn’t exist or 404 Not Found, that means that you received a 404 error, which is a type of status code you get back from an HTTP request when the server could not find the requested resource.

Now we can look more closely at the components of URL, through the Mozilla example here https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Learn/Common_questions/Web_mechanics/What_is_a_URL#scheme.

So first we have the scheme or protocol, which tells the browser how to communicate with the server:

It’s important to note that websites, web browsers, and search engines are all software applications that utilize the HTTP protocol to communicate with web servers, but they differ in function:

- a website is a collection of web pages and related content that is identified by a common domain name and published on at least one web server, like our course website. A website might have internal and external links on it as well.

- a web browser is a software application that is used to access websites and view web pages, like Google Chrome or Firefox or Safari. So while you can open any HTML document in a web browser, you can also use a web browser to access websites that are hosted from other servers.

- a search engine is a web service like Google or DuckDuckGo that allows users to search for content on the web, usually accessed from a web browser. These search engines often crawl websites via URLs to index the content of the web.

So now that we have some terminology, we can look at some of the rest of the URL.

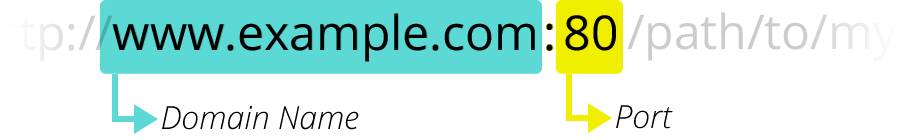

What is a Domain Name?

Next we have the authority or domain name, which is the name of the server that hosts the website:

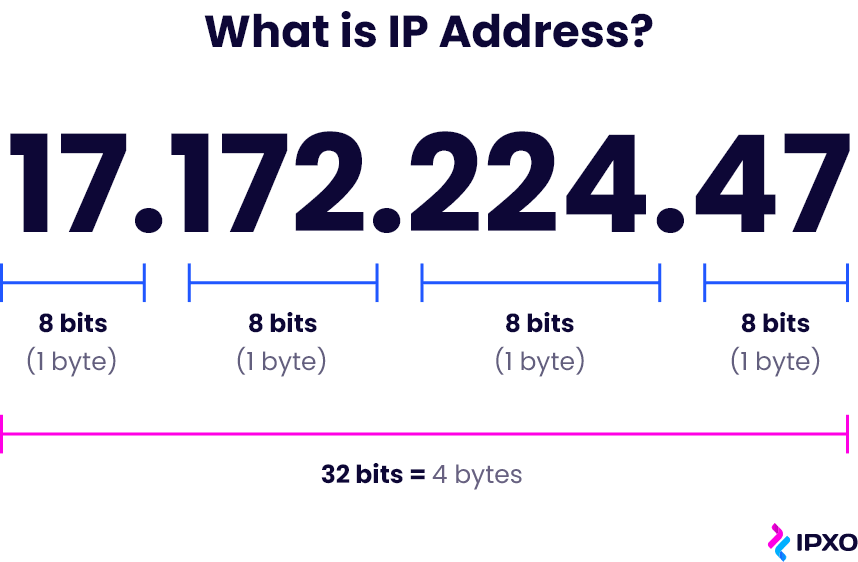

Originally, when you used the internet you would access other websites using something called an IP address, which is a series of numbers that identifies a particular computer on the internet. You can see an example of an IP address here:

For example, the 1995 classic, thriller movie The Net starring Sandra Bullock as a systems analyst who “must use her computer skills to uncover the truth and clear her name.” In the movie, she searches using IP addresses which you can watch a clip of here: https://youtu.be/M1K-B8QVLyo?t=242.

IP Addresses are still used today, but they are not very human readable or user friendly (though we will be seeing some in action today), so instead, we use domain names. Domain names are part of the Domain Name System (DNS) which is often described as a “phone book” or “address book” that translates IP addresses of servers into easier to understand domains.

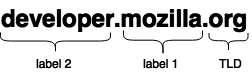

Here’s an example of a domain name:

In this explanation from Mozilla https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Learn/Common_questions/Web_mechanics/What_is_a_domain_name, they outline that there are two general main components to a domain name:

- the top-level domain (TLD), which is the last part or suffix of the domain name, like

.comor.orgor.edu. These are registered and managed by a central organization called ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers). As you can imagine, there’s a long history and fraught politics around TLDs, since they are often tied to nation states (for example,.ukor.ca). Notably, while there is.usfor the United States, most US websites use.comor.govif they are government-related. If you’re curious to learn more I would recommend this blog post on dead-TLDs https://astrid.tech/2022/04/05/1/dead-tlds/ and checking out the rich literature on Internet Governance with books like Milton Mueller’s Networks and States or Laura DeNardis’ The Global War for Internet Governance. - the other part of a domain name is the second-level domain (SLD), which is the part of the domain name that is to the left of the TLD, like

mozillainmozilla.org. These are managed by domain name registrars, like GoDaddy, and are registered by individuals or organizations. One key thing to understand is that you can purchase a domain name through registrars but not in perpetuity. This leads to not only needing to renew your domain names, but also to the rise of domain name speculation, where people purchase domain names in the hopes of selling them for a profit. You can read more about this in this fascinating article by Ingrid Burrington on visiting a Domain-Names Conference https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/02/domain-names-dot-horse/516438/.

So in the case of the Mozilla example, we have a subdomain developer and a second-level domain mozilla and a top-level domain org.

This is all very technical, but we can start to try this out if we attempt to host our HTML pages.

Hosting HTML Pages with GitHub Pages

While we have primarily been using GitHub for its versioning and collaboration features, it also has a feature called GitHub Pages that allows you to host static websites for free. This is a great way to share your work with others, and to learn more about how the web works. We will be building static web sites later this semester, but to get our feet wet, we can start by hosting our HTML pages.

How to Host HTML Pages with GitHub Pages

First, you need to create a new repository on GitHub. You can do this by clicking the + in the top right corner and selecting New Repository.

As a user on GitHub, you can create a custom website that is hosted on GitHub Pages. This is a great option for creating a personal website, or a website for a project. This website is hosted at the github.io domain name so you don’t have to pay for a domain name. However, to make this domain you need to create a repository with a specific name: your username. So for example, my GitHub username is ZoeLeBlanc so I need to create a repository called ZoeLeBlanc.github.io to generate my website. Since I already did that many moons ago, to show you what this looks like, I’ve created a new a username called TestZoe, so my repository is called testzoe.github.io.

When you create your repository, you need to make sure it is Public and you can add a README.md (though that is optional).

Once you have your repository, the next step is to add some web files. The most basic file you can add is an index.html file.

Once you’ve created your index.html file, you can either leave it blank or add some HTML code. Now the key thing is to remember to commit your HTML page. Remember committing is how we save things on GitHub. So you can either commit via the command line with your VS Code Terminal or via the GitHub website.

Now, GitHub should start automatically hosting your website at https://yourusername.github.io.

You’ll notice you don’t need to configure any Actions (though you can for HTML), and that’s because this is a special type of repository on GitHub, so any HTML files you add will automatically be hosted but that will not happen in other repos.

You can still see how GitHub is deploying your site by clicking on the tab called Actions:

You should see some green lines and checks, all of which indicates your site is live.

You can find see this live here https://testzoe.github.io/.

Homework

Doing It Live: Hosting Your HTML Page Assignment

Now that you understand how the web works, how to write HTML, and how to create a website on GitHub Pages, it is time to put your knowledge to the test. Your assignment is to follow the steps above to create a repository with your GitHub username, upload your HTML file from the Intro to HTML assignment, and then have it correctly host via GitHub Pages.

Once you’re site is live, post the link to your HTML page via github.io to our next GitHub Discussion thread https://github.com/ZoeLeBlanc/is310-computing-humanities-2024/discussions/3.

Already hosting a website via GitHub Pages?

Then feel free to skip this assignment, and just post the link to your existing website, as well as your GitHub repository so we can see your HTML code.