Web Scraping

Now that we have learned how to work with Python modules and read and write files, we can start to think about how to get data from the web. This is a very important skill for a digital humanist, as many of the sources we might want to work with are online.

What Is Web Scraping and Why Is It Useful?

So far when it comes to working with the web, you have been creating your own HTML pages and hosting them via GitHub. But we can also use Python to interact with the web in a different way: by scraping data from web pages. The data we extract is exactly the same as what you have been writing, so elements like headers, paragraphs, and links, etc.

Web scraping can be incredibly useful considering how much data is available on the web and how little of it is often put into tabular format. For example, you might want to scrape a web archive to get data for a research project, or you might want to scrape a social media site to get access to data that isn’t available through their API.

Web scraping is also what we use to preserve the web. Remember the Wayback Machine? That’s a web archive that uses web scraping to save web pages. The way it works is that it uses a web crawler to find links to web pages and then it uses web scraping to save the content of those pages.

This method has also been used by scholars to do community-driven data preservation. For example, when Russia invaded Ukraine, a group of scholars and librarians founded the Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online (SUCHO) group and used web scraping to preserve the content of Ukrainian websites https://www.sucho.org/. This was important because if servers are bombed, the content of those websites would be lost forever.

Is Web Scraping Legal or Ethical?

Technically, most publicly available internet data is considered legal to collect, even if it’s not explicitly licensed. In 2019, “the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that automated scraping of publicly accessible data likely does not violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA).”1 However, there are some important caveats to this. For example, this ruling only applies to US based websites and the laws in other countries might be different. One of the more recent and important European developments was the passing of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018, which has implications for web scraping. In particular, the GDPR bans the scraping of emails and personal names from websites. More recently, a consortium of regulators from multiple countries released a joint statement warning social media companies that they must protect user data from scraping.2

In terms of ethics, web scraping can be a bit of a grey area. It’s generally considered ethical to scrape publicly available data, but it’s not ethical to scrape data from a website that has a terms of service that prohibits scraping (though it can be difficult to find that out if you remember the art installation from last week’s class on terms of service https://www.designboom.com/readers/dima-yarovinsky-visualizes-facebook-instagram-snapchat-terms-of-service-05-07-2018/).

A more obvious example of a website banning scraping is if it prohibits scraping in its robots.txt file. A robots.txt file is a file that websites use to tell web crawlers which pages they are allowed to scrape.

For example,the above image is of the robots.txt file for the New York Times website is https://www.nytimes.com/robots.txt. We can see that it lists a number of pages that are not allowed to be scraped (those are the ones with the Disallow directive). You might also come across robots.txt files that have a Crawl-delay directive, which tells web crawlers how long to wait between requests. The reason this is important is that if you try to web scrape a website that has a robots.txt file that prohibits scraping, you could be banned from the website. This is because the website might think you are a web crawler and not a human, and it might block your IP address.

What to collect and how to collect it is a big part of the ethics of web scraping. Melanie Walsh has a great overview of some of these tradeoffs:

Just because something is legal or gets approved by an IRB does not mean it is ethical. Collecting, sharing, and publishing internet data created by or about individuals can lead to unwanted public scrutiny, harm, and other negative consequences for those individuals. For these reasons, some researchers attempt to anonymize internet data before sharing it or before publishing an article that cites a post specifically. Yet anonymizing internet data also does not give credit to internet users as creators and authors.

There is no single, simple answer to the many difficult questions raised by internet data collection. It is important to develop an ethical framework that responds to the specifics of your particular research project or use case (e.g., the platform, the people involved, the context, the potential consequences, etc.).

In my own research, I have started seeking explicit permission from internet users when I want to quote them in a published article. In this book, I only share internet data that meets a certain threshold of publicness, such as tweets from verified Twitter accounts or Reddit posts with a certain number of upvotes. This is an approach that I have developed based on some of the models and readings included below.

IRB refers to the Institutional Review Board, which is a committee that reviews and approves research involving human subjects at universities, and most of the time, web scraping or accessing digital data is considered not to be human subjects research. However, even if we don’t need IRB approval, it’s still important to think about the ethics of web scraping and to consider the potential consequences of our actions. I personally think Walsh’s approach is a good one: to think about the specifics of your research project and to develop both a legal and an ethical framework that responds to those specifics. And also to think about the consent of the people whose data you are collecting. There’s no one size fits all answer, but we should always think about not only if we can collect data, but also if we should and how we should.

As you can see above, Walsh also has a great overview of different strategies and resources for this type of work, so highly recommend visiting the original chapter to explore these further in depth https://melaniewalsh.github.io/Intro-Cultural-Analytics/04-Data-Collection/01-User-Ethics-Legal-Concerns.html.

Web Scraping with Python

Now that we have a sense of web scraping generally, it’s time to try it out in Python.

Installing Required Packages

The first step is to install our required packages. We’ll be using the requests package to get the web page and the beautifulsoup4 package to parse the web page. We will be installing these into a virtual environment. If you have yet to set up a virtual environment, you can follow the instructions in the previous lesson.

source is310-env/bin/activate

pip3 install requests beautifulsoup4

We previously discussed Python libraries when we talked about classes and file input and outputs, but let’s dig in a bit deeper.

Library

- There’s a lot of different definitions for this term, but most generally you can think of this as a collection of software that’s directly used by other software. Most often, this will be a generalizable piece of logic that is useful to bundle separately so that other, unrelated pieces of software can use it. Because it’s an informal term in Python and not a specific, technical one, it’s more useful to think about libraries in terms of how code is organized. Used in this way, the concept of “software libraries” spans many different programing languages and development contexts: we have Python libraries, C++ libraries, Javascript libraries, operating system libraries, etc.

- Let’s consider libraries that we’ve used. The Python Standard Library is the most obvious example which encompasses many different purposes and packages (more on that later), but is unified in that it is included in all Python installations so that Python code that’s written using the Standard Library will run on any compatible Python environment of the expected version. Parts of the Standard Library that we’ve used before include packages like pathlib.

- There are also third-party libraries that people build in Python, which can be found on The Python Package Index (PyPI) https://pypi.org/. These are usually less expansive than the Standard Library, but can be useful because they are written for specialized tasks. This week, we’ll take a look at Beautiful Soup, which is analogous in scope to packages like pathlib. In fact, third party libraries are often organized into a single package. A library like Beautiful Soup can best be thought of in terms of purpose: you want to accomplish the a particular, common task like scraping a website and Beautiful Soup helps accomplish it.

Package

- A package is a formal term in the Python context. It’s a specific organization of code which all lives in a single directory. Libraries sometimes (often) consist of a single package (e.g. PathLib or BS4), so the term is sometimes (often) used interchangeably. Packages are the basic unit by which we install and use libraries. So when we type

pip3 install beautifulsoup4into the terminal, we’re installing thebeautifulsoup4package.

This is very detailed, but just remember that while these terms are often used interchangeably, a package is a more specific concept referring to the structure and distribution of code, whereas a library is a broader concept referring to reusable code functionality.

Here, confusingly, the name of the package on PyPI (beautifulsoup4) doesn’t match the actual Python code package (bs4). Which is why we always read the documentation, which is available here https://www.crummy.com/software/BeautifulSoup/bs4/doc/!

So let’s try using this library. First, we need to import it into our Python file. If you don’t have a file yet, would highly recommend making a new folder in your is310-coding-assignments called web_scraping and then creating a new file called web_scraping.py. Then you can add the following code to your file:

We use Beautiful Soup in our Python code with code that looks like this:

import bs4

soup = bs4.BeautifulSoup(html_doc, 'html.parser')

# 'bs4' is the package, 'BeautifulSoup' is a class defined inside the package definition

or

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup(html_doc, 'html.parser')

# this code is equivalent

We can also use the star symbol, which often means “all” or “any”, to import all the modules (aka Classes and functions) in the package:

from bs4 import *

soup = BeautifulSoup(html_doc, 'html.parser')

# imports * imports all modules in a package

In these examples, we can either the bs4 package directly or, using the from keyword, import modules from with that package.

While technically we can do the from bs4 import *, that’s usually only good for when you’re testing out code. Otherwise, for people just reading through our code, there’s no obvious connection between the bs4 package and the BeautifulSoup class. It would take some deeper understanding of BeautifulSoup or at least chasing down some its documentation.

Scraping A Web Page

Now that we have installed our packages, let’s try scraping a web page. We’ll start by checking the version of the beautifulsoup4 package that we installed. Let’s update our code:

import bs4

print(bs4.__version__)

When we save and run this file, we should see the version of the beautifulsoup4 package that we installed. If you don’t see a version number, you might have installed the package incorrectly. If you see a version number, you’re good to go!

Looks good so now let’s take a look at the page we’ll be scraping, https://humanist.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/. This is a web archive of the Humanist Listserv that was first started in 1987 by Willard McCarty, as a “a BITNET (NetNorth in Canada) electronic mail newsletter for people who support computing in the humanities.”3 For those unfamiliar, in the early days of the internet, listservs were a popular way to communicate with people who shared your interests. They were like a cross between a forum and an email list. The Humanist Listserv is still active today and is a great resource for people interested in the digital humanities.

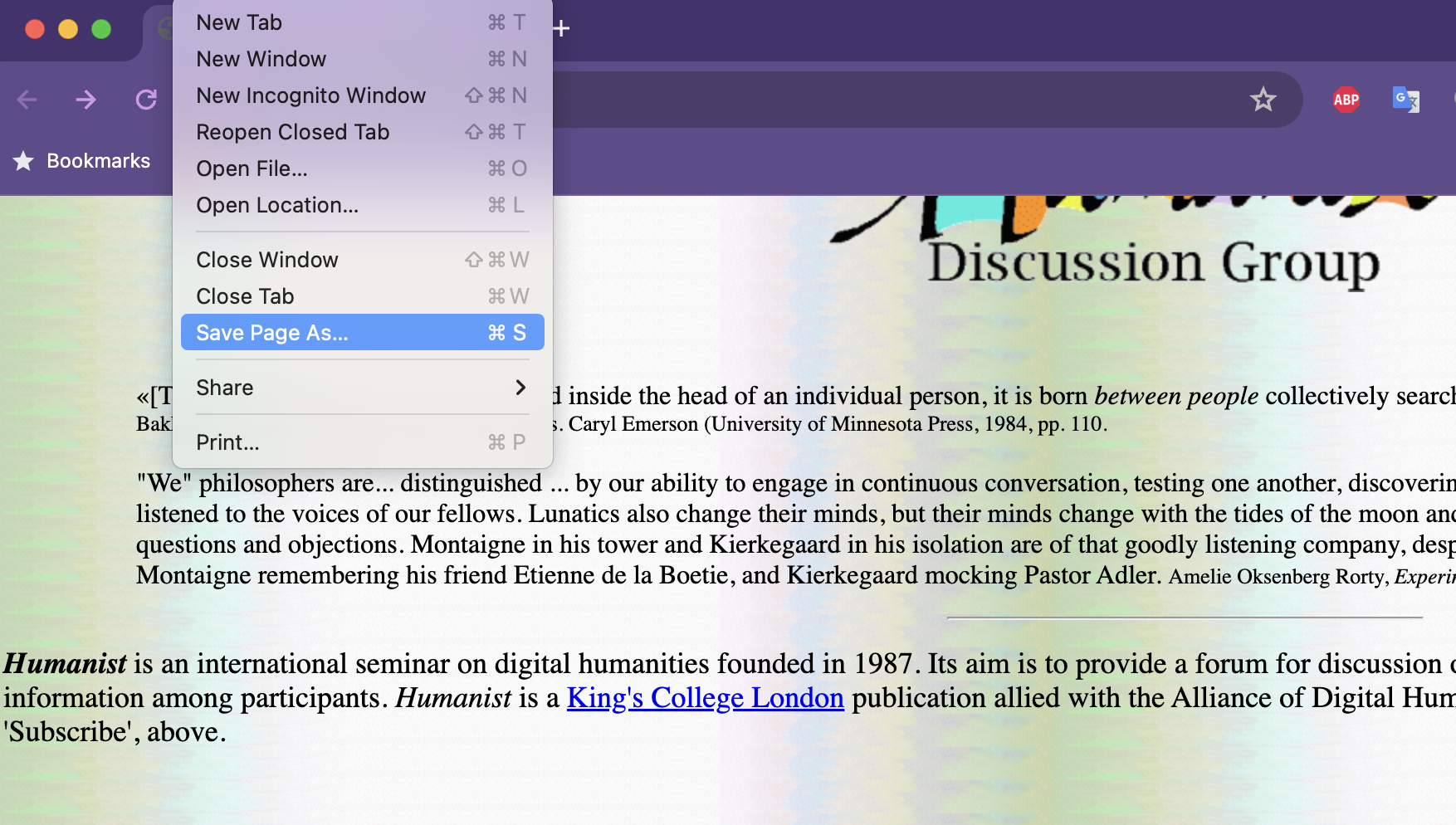

First, let’s save this homepage as a new file called humanist_homepage.html in the same directory as our web_scraping.py file.

We can easily save this page as an HTML file by right clicking on the page and selecting “Save As” and then saving it as humanist_homepage.html.

Now we can try scraping that page!

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

soup = BeautifulSoup(open("humanist_homepage.html"), features="html.parser")

print(soup.prettify())

You can see we now have the full html page in all it’s weirdly organized HTML glory.

Now let’s figure out how to use BeautifulSoup by going to the documentation for the library

We can see here that soup is an instance of a bs4.BeautifulSoup class. This is an object that represents the whole of the document. The other important class we will use is the Tag class, which represents an html tag. These two classes actually share many of the same methods: we can use get_text() on either a BeautifulSoup or a Tag to extract just the text that they contain.

We can also use the find_all() method that they share to search with either the whole document or within the tag. Remember that tags can be nested within each other.

Let’s try and get all the links on our webpage.

links = soup.find_all('a')

for link in links:

print(link)

We can see that we are getting lots of different links here. Everything from the Home link (which is usually just a / on most websites) to links to all the volumes.

So now we need to decide what we want to keep and what we don’t 🤔. Let’s take a look at the basic structure of the html file, using the inspect feature in your browser and think about what we might want to scrape.

Quick Exercise

How could we get just the Volume links? We can use the find_all() method to get all the links in the document and then use get_text() to get the text of each link.

Try completing the code below in your web_scraping.py file to get just the Volume links.

links = soup.find_all('a')

for link in links:

print(link)

## Code goes here

Requests and the Web

We are now officially scraping a web page 🥳!! But what if we wanted to scrape more than one? Saving each manually would get tiring really quickly!

Instead we can use another Python library called requests to programmatically get each web page. We already installed requests initially so now we need to import it into our web_scraping.py file.

Let’s also take a look at the documentation for the requests library https://requests.readthedocs.io/en/latest/. From this documentation, we can see that the requests.get() method is used to get a web page. This method returns a Response object, which has a text attribute that contains the HTML of the page.

Let’s try it out with our Humanist Listserv page.

import requests

response = requests.get("https://humanist.kdl.kcl.ac.uk/")

print(response.status_code)

print(response.headers)

So what is this code and information exactly?

Well, first we are importing the requests library and then we are using the built in get() method to get the web page. This method returns a Response object (aka Class), which has a status_code attribute that contains the status code of the request and a headers attribute that contains the headers of the request.

If you remember our introduction to the Web lesson, we talked about how the web works, and specifically how when you go to a URL, a server checks if you’re allowed to access that data and if you are returns a status code of 200, along with the data. This is the exact same concept when you’re working with requests in Python. So you can think of requesting a website as the same as going to a website in your browser.

It is always good to check the status_code when you are working with requests because if you get a 404 status code, that means the page doesn’t exist. If you get a 403 status code, that means you don’t have permission to access the page. If you get a 500 status code, that means there’s an error on the server. And so on.

Requesting and Souping Humanist

Now that we have requests working, rather than using the open() method to open our HTML file, we can use the text attribute of the Response object to get the HTML of the page. Let’s try it out.

soup = BeautifulSoup(response.text, "html.parser")

print(soup.prettify())

We can see that we are getting the same HTML as we did when we opened the file manually. This is great because it means we can now scrape any web page we want, not just the ones we have saved locally.

Now let’s see if we can use our code from earlier to get every volume link on the page and use that to scrape the text of each volume.

links = soup.find_all('a')

for link in links:

if "Archives" in link.get('href'):

print(link.get_text())

volume_url = "https://humanist.kdl.kcl.ac.uk" + link.get('href')

volume_response = requests.get(volume_url)

volume_soup = BeautifulSoup(volume_response.text, "html.parser")

print(volume_soup.get_text())

This code is a bit more complicated than what we’ve done before, but it’s not too bad. We are using the find_all() method to get all the links in the document and then using the get_text() method to get the text of each link. We are then using the get() method to get the href attribute of each link, which contains the URL of the link. We are then using the requests.get() method to get the web page and the text attribute of the Response object to get the HTML of the page. We are then using the get_text() method to get the text of the page.

Our final step would be to save this text to a file. We could either create text files, but in this case it might be easier to create a csv file. To do that we would need to use the csv library, which is part of the Python Standard Library. We would also need to use the open() method to open a file and the write() method to write to the file. We would also need to use the writerow() method to write a row to the file.

import csv

with open('humanist_volumes.csv', 'w') as file:

writer = csv.writer(file)

# Write the headers

writer.writerow(['Link', 'Volume Text'])

for link in links:

if "Archives" in link.get('href'):

volume_url = "https://humanist.kdl.kcl.ac.uk" + link.get('href')

volume_response = requests.get(volume_url)

volume_soup = BeautifulSoup(volume_response.text, "html.parser")

writer.writerow([link.get_text(), volume_soup.get_text()])

Now we have a csv file with all the volume links and the text of each volume. We can use this file to do whatever we want, like analyze the text of each volume or create a visualization of the volume links.

However, if you open this file, you’ll see it’s a bit of a mess. Why might that be? Part of your homework is to figure out how to fix this!

Web Scraping Assignments

Now that you have learned the basics of web scraping, it’s time to try them our for your homework assignments. In your is310-coding-assignments, you should create a new directory called web_scraping_assignments and once you have completed the assignments below, you should push them up to your Github repository. You should then share a link to your folder in this week’s discussion thread https://github.com/ZoeLeBlanc/is310-computing-humanities-2024/discussions/4.

If you have any issues you can always message the instructors via Slack.

Pudding Scripts Web Scraping

Building from Melanie Walsh’s example in https://melaniewalsh.github.io/Intro-Cultural-Analytics/04-Data-Collection/02-Web-Scraping-Part1.html#why-do-we-need-to-scrape-at-all, try using requests and BeautifulSoup to get the data from the Pudding Film Movie Dialogue article we read.

-

We have already downloaded the csv with the Pudding Film Movie Dialogue article URLs. You can download the file by clicking here. However, unfortunately this original file now contains redirects to sites that are nsfw content, so I have tried to remove those and you can download this cleaned file here here. Be aware that some of these sites will have 400 errors so you may need to test for the response status code.

-

Once you have the correct file, you will need to create a new script called

pudding_movie_dialogue.pyand use the libraries we’ve explored today to read in this file, loop through each script, and access the script data. -

Once your code is working, you should save the results to a new csv file called

pudding_movie_dialogue.csvin the same directory as your script. Because scripts are long, I would recommend only saving the first 1000 characters of each script to this file (which you can do by indexing).

Complete Humanist Volumes Web Scraping (Optional and Advanced)

We have already started scraping the Humanist Volumes, but we need to clean up the data. If you look through some of the volume links, you’ll notice that some volumes have links to the various email threads, whereas others just have the email threads on the page. This means that we are some times getting links and other times getting text. We need to figure out how to get just the text of the email threads and then save that to a csv file.

Your goal for this assignment is to build off our existing code and your explorations of the website to get just the text of the email threads and links to the volumes and then save that to a csv file, called humanist_listserv_volumes.csv. This is a bit of trick assignment, so would highly encourage you to look around the website carefully. The volumes are quite long, so would again recommend only saving the first 1000 characters of each volume to this file.

-

Crocker, Camille Fischer and Andrew. “Victory! Ruling in hiQ v. Linkedin Protects Scraping of Public Data.” Electronic Frontier Foundation, September 10, 2019. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2019/09/victory-ruling-hiq-v-linkedin-protects-scraping-public-data. ↩

-

Lomas, Natasha. “Social Media Giants Urged to Tackle Data-Scraping Privacy Risks.” TechCrunch (blog), August 24, 2023. https://techcrunch.com/2023/08/24/data-scraping-privacy-risks-joint-statement/. ↩

-

“Humanist (Electronic Seminar).” In Wikipedia, September 30, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Humanist_(electronic_seminar)&oldid=1113204927. ↩