Introduction to Formatting and Organizing Data

What is a file and why are there so many formats?

This is a huge topic in LIS and CS but to put it simply a file is a collection of data stored in a single unit, identified by a filename. It can be a document, an image, a video, a sound, or any other collection of data. The file extension is the part of the file name after the period. For example, in the file name DH-Tool.md, the file extension is .md. The file extension tells the computer what type of file it is and what program to use to open it.

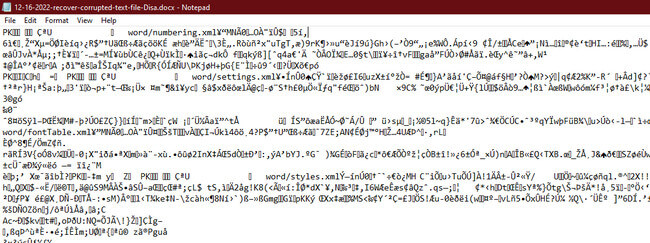

There are many different file formats and each one has its own purpose. For example, a .docx file is a Microsoft Word document, a .jpg file is an image, and a .mp3 file is an audio file. Some file formats are proprietary, meaning they are owned by a company and can only be opened by certain programs. For example, .docx files can only be opened by Microsoft Word. So if you try to open up a word document in a PDF Viewer you might see what looks like a bunch of gibberish.

This gibberish is actually the code that makes up the file, but since the PDF Viewer doesn’t know how to read the code it just shows you the code itself rather than the data stored in the files.

Other file formats are open source, meaning they are not owned by a company and can be opened by many different programs. For example, .txt files are plain text files that can be opened by any text editor.

What is plain text and Markdown?

Plain text is a file format that only contains text and no formatting. It is the simplest file format and can be opened by any text editor. Markdown is a plain text file format that uses symbols to add formatting to the text. For example, if you want to make a word bold you would put two asterisks on either side of the word.

**bold**

If you want to make a word italic you would put one asterisk on either side of the word.

*italic*

If you want to make a list you would put a dash in front of each item.

- item 1

- item 2

- item 3

If you want to make a heading you would put a hashtag in front of the heading.

# heading 1

## heading 2

### heading 3

These types of file formats are incredibly popular in DH for a few reasons. First, they are free to use and are more sustainable long term since they do not require specialized software to open. Second, this interoperability makes them easier to share and collaborate on, as well as use in a variety of DH Tools. Finally, the use of such file formats also preserves this data for future use. For example, if you have a .docx file and Microsoft Word goes out of business, you will no longer be able to open that file. However, if you have a .txt file you will always be able to open it in any text editor.

The key thing to understand is that every file format has a history and is the product of multiple decisions and communities. In the case of Markdown, it was created by John Gruber with help from Aaron Swartz in 2004. The goal was to create a file format that was easy to read and write, and could be converted into HTML. They also wanted to create a file format that was easy to use and could be used by anyone. You can read more about the history of Markdown, in Bednarski, Dawid. “The History of Markdown: A Prelude to the No-Code Movement.” Taskade Blog, March 25, 2022. https://www.taskade.com/blog/markdown-history/.

It’s important to understand that Markdown has this history because many flavors of Markdown exist, and standardization of Markdown has been an ongoing project. For example, GitHub Flavored Markdown (GFM) is a flavor of Markdown that was created by GitHub in 2009. It is a superset of Markdown, meaning it adds additional features to Markdown. For example, GFM allows you to create tables in Markdown, which is not possible in regular Markdown. You can read more about GFM in “GitHub Flavored Markdown Spec.” GitHub, 2022. https://github.github.com/gfm/.

This figure shows some examples of how Markdown is written depending on the Platform and standards. You can also see some of the discussions that go on to help shape these standards through the various repositories on GitHub that host the standards. For example, CommonMark is another popular Markdown style and improvements to it are discussed in this repository https://github.com/commonmark/commonmark-spec/issues.

Popular File Formats in DH

Understanding some of the tradeoffs and histories of file formats helps us consider increasingly popular file formats in DH. We have already discussed Markdown, but we will also be looking at two others: JSON and CSV.

JSON

JSON stands for JavaScript Object Notation and is a file format that stores data in a key-value pair. For example, if you wanted to store our data from assignments this week you might write it like this:

{

"DH Tool": "GitHub",

"Found by": "Zoe LeBlanc"

}

This file format is popular in DH because it is easy to read and write, and can be used in a variety of programming languages. It is also a popular file format for sharing data across the web. You can read more about JSON in “JSON: JavaScript Object Notation.” MDN Web Docs, 2022. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/JSON.

We won’t be using this file format much in this course, but it’s important to know it exists since many datasets are available as JSON files. These files will have the file ending of .json and will always have the curly brackets, and values separated by colons and listed with commas.

CSV

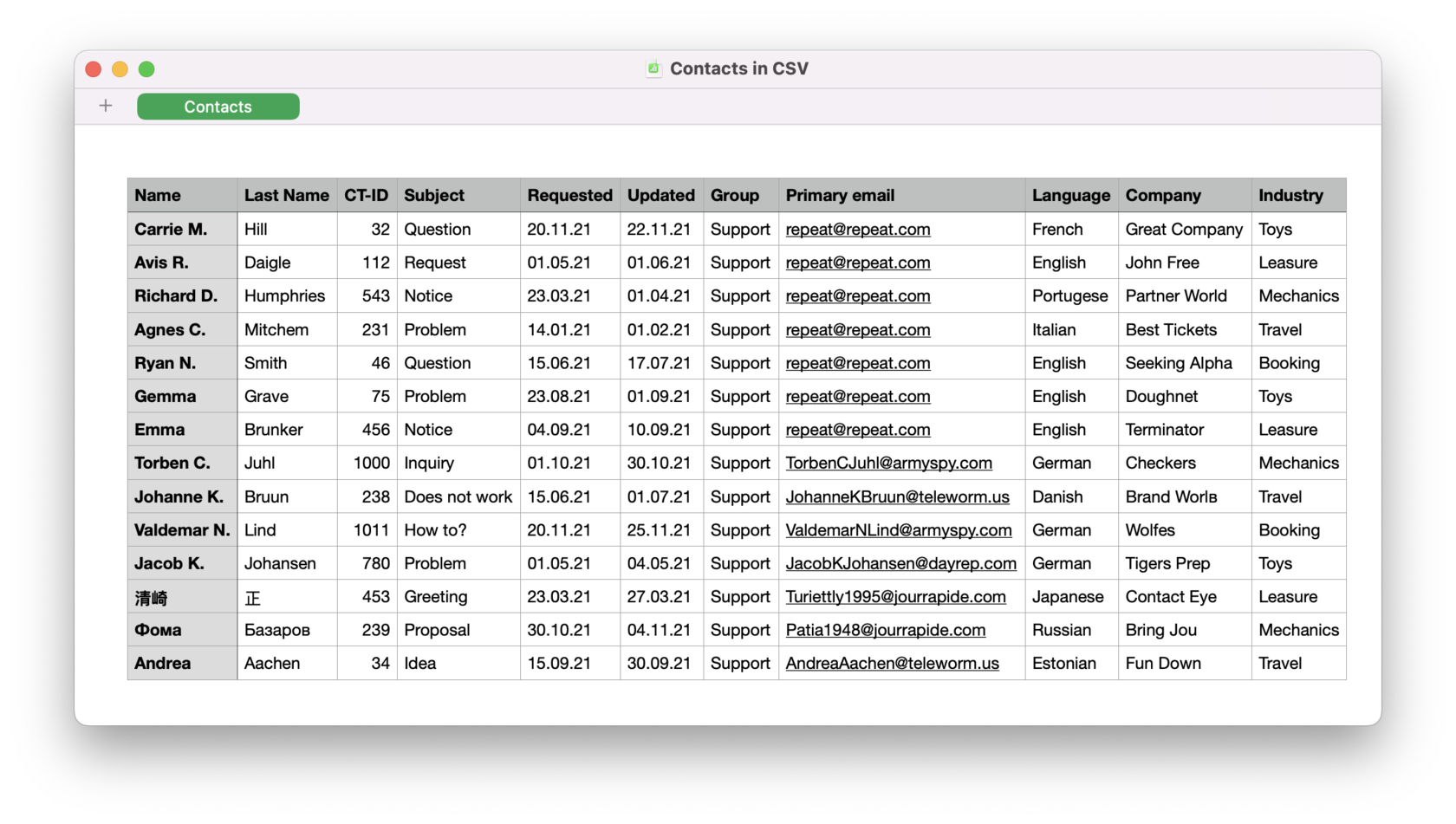

The other incredibly popular file format that you likely have already used before and that we will use a lot in this course is CSV. CSV stands for Comma Separated Values and is a file format that stores data in a table. For example, if you wanted to store our data from assignments this week you might write it like this:

DH Tool, Found by

GitHub, Zoe LeBlanc

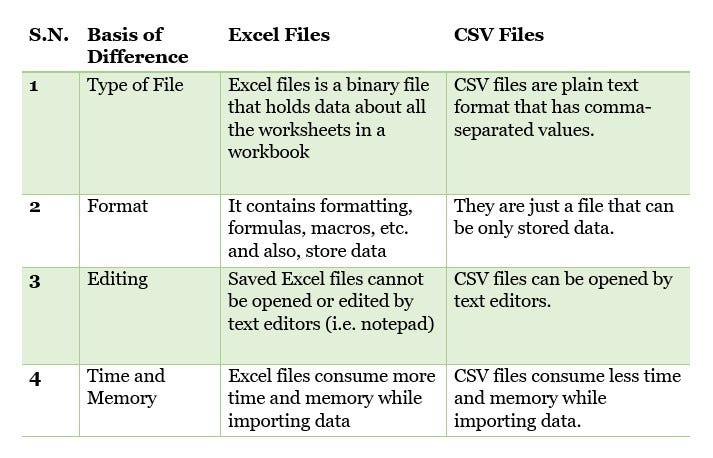

CSVs are a usually read by spreadsheet software, like Excel or Google Sheets and have the file ending of .csv. Unlike .xlsx files, which are proprietary to Microsoft Excel, CSVs are open source and can be opened by any spreadsheet software.

CSVs have a long history as well and the file format was first created in the 1970s. But as we we will discuss more next week, the act of putting data into tables has an even longer history.

Data Creation & Discovery Assignment

In class, we worked through taking everyone’s submission of a DH Tool and turning it into a dataset. You find last week’s DH Tools submissions in this discussion forum on our GitHub repo https://github.com/ZoeLeBlanc/is578-intro-dh/discussions/2 and our starting dataset at this Google Sheets link here.

For homework this week, your goal is to finish inputting the remaining submissions from the GitHub repository, but also consider how you might want to organize this data, label these columns, and what other data you might want to add. One key thing is that for the moment you should aim to have ZERO empty cells. This is a good practice for working with data in general, but also will help us when we try to join this dataset with other datasets.

As I mentioned in class, we will be trying to join this dataset to other ones from this week, including the datasets from “Which DH Tools Are Actually Used in Research?,” December 6, 2019. Barbot, Laure, Frank Fischer, Yoann Moranville, and Ivan Pozdniakov. “Which DH Tools Are Actually Used in Research?,” December 6, 2019. https://weltliteratur.net/dh-tools-used-in-research/ and then the data from Index of DH Conferences https://dh-abstracts.library.virginia.edu/downloads.

So some things to consider are:

- Are there structures you want to emulate from these examples?

- Do you want to keep the current structure and have to fill in the remaining data? Or change the structure?

To help you do this exercise, here’s a few steps to follow:

- You’ll need to either copy or download the data from the Google Sheet. To do this, go to File > Download > Comma-separated values (.csv, current sheet). This will download the data as a CSV file. You’re welcome to use whatever software you prefer to enter data.

- Once completed, upload your spreadsheet to GitHub and create a new Markdown file to document your dataset, similar to the data dictionary on the Index of DH Conferences.

- If you are having trouble using

github.dev, I’m actively investigating what is going wrong but in the interrim, you can link to a Google Drive Folder with your data and documentation (the documentation can be a Google Doc, if you are struggling to create a Markdown file).

- If you are having trouble using

- Finally submit a link to our next GitHub forum discussion https://github.com/ZoeLeBlanc/is578-intro-dh/discussions/3.

Bonus Assignment

If you have time and interest, you are also welcome to post a link to a DH dataset in this forum. Finding existing data can be faster than having to build some by hand, so this may be useful for you as you start to work on developing your DH Workshop.

Some places to look include:

- The Journal of Open Humanities Data https://openhumanitiesdata.metajnl.com/

- HumanitiesData.com https://humanitiesdata.com/

- Kaggle https://www.kaggle.com/datasets?fileType=csv

Additional Resources

- Gregory, Ben. “Data Formats 101.” Astronomer, n.d. https://www.astronomer.io/blog/data-formats-101.