Getting Data From APIs

So far in class we have briefly mentioned APIs (for example, the Genius and Spotify API), but haven’t yet discussed what they are or how to use them. This week we will start to work through the basics of using APIs to get data from the web.

What is an API?

API stands for Application Programming Interface.What does that mean exactly?

While according to Wikipedia,

An application programming interface is a connection between computers or between computer programs. It is a type of software interface, offering a service to other pieces of software. A document or standard that describes how to build or use such a connection or interface is called an API specification.

But that probably leaves you with more questions than answers.

Let’s try looking at specific API to figure out what this means. We’ll be working with the DPLA API (the same one that is our reading of Yanni Alexander Loukissas, All Data Are Local).

If you pull up their documentation for their API https://pro.dp.la/developers/api-basics/, you’ll notice they begin with a helpful explanation for what is an API.

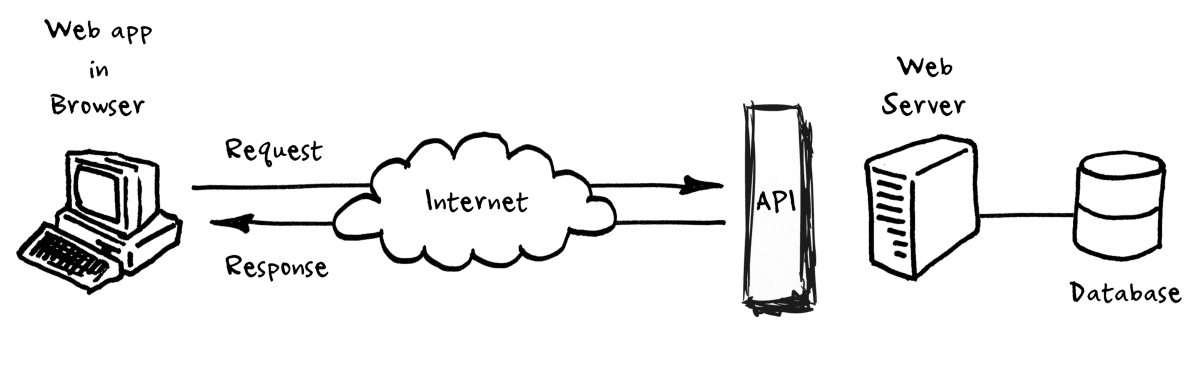

In this documentation, the talk about APIs as a type of language similar to HTTP. To help us understand this connection, let’s also take a look at this figure:

You’ll notice that we have a web browser that is using the “internet cloud” to make requests and get responses from an API that is connected to a web server and a database. This might seem complex, but we’ve seen a similar relationship when we talked about how the web works. We talked previously about how web browsers use HTTP to make requests and get responses from web servers, this is the same idea. APIs are just a way to get data from a server, similar to how we get web pages from a server, but instead of storing the data in a webpage (aka an HTML document), the data is stored in a database. For example, when you use a weather app, or really any app on your phone, that app is using an API to get the weather data from a server.

Databases might also sound intimidating, but they are just a way to store data, similar to csvs or excel files. The difference is that databases are designed to store large amounts of data and to allow that data to be accessed and manipulated quickly, usually using something called SQL (Structured Query Language).

Rather than going to a URL in your browser, an API lets us send a similar request to a server, and then we can get the data we want. If you want a bit more in-depth introduction you might check out this medium post https://medium.com/epfl-extension-school/an-illustrated-introduction-to-apis-10f8000313b9.

Big takeaway is to realize that so far we have been getting data by either downloading CSVs or scraping from the web. APIs let us get usually larger amounts of data that would be either difficult to download or difficult to scrape.

So let’s try this out with the DPLA API.

Working with DPLA API

There’s a few ways we can work with the DPLA API. First we are going to be working with the requests library we used in the Intro to Web Scraping lesson. But if you are having issues authenticating with the API, you can jump ahead and use the DPyLA library, which is a Python library to work the DPLA API.

Authenticating with DPLA

Our first step when working with an API is to authenticate. This sound intimidating but you do it all the time whenever you login to your email, DUO, social media, etc…; it’s just usually this is handled automatically by your browser. Because we aren’t using a browser with APIs, we need to do this explicitly by making a request to the API to get an authentication key and token.

For DPLA we will follow these instructions https://pro.dp.la/developers/policies#get-a-key, but it’s worth noting that many APIs have different ways of authenticating so you should be sure to read their documentation (usually available under developer documentation, like this one from the Spotify API https://developer.spotify.com/documentation/general/guides/authorization/).

First, let’s get our DPLA token!

On Macs/WSL, open your VS Code terminal and type:

curl -v -XPOST https://api.dp.la/v2/api_key/YOUR_EMAIL@example.com

On Windows, open your VS Code PowerShell terminal and type:

Invoke-WebRequest -Uri ("https://api.dp.la/v2/api_key/YOUR_EMAIL@example.com") -Method POST -Verbose

In both examples, replace YOUR_Email@example.com with your email (can be any email address). If you run into issues, again feel free to jump ahead and authenticate with DPyLA.

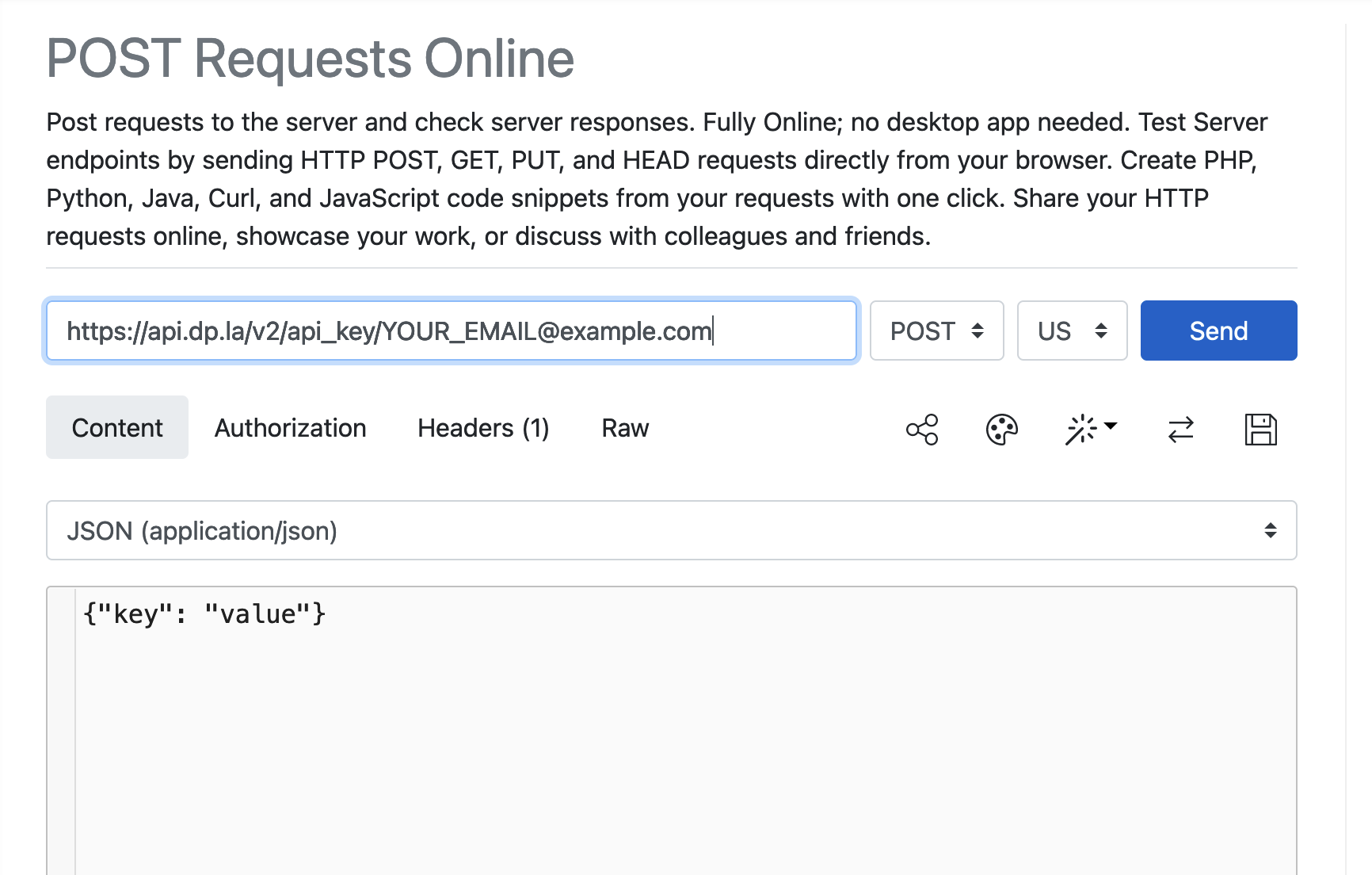

If you are having issues with either of these options, you can use websites like https://reqbin.com/post-online, which allow you to mimic the curl command in a web browser.

Once you’ve completed that step, go to your inbox and you should see an email from the DPLA with your API key, which is a long list of alphanumeric characters.

Most APIs require you to authenticate in some way, and this is usually done by providing an API key. This key is unique to you and is used to identify you when you make requests to the API. It’s like a password, so you should keep it secret and not share it with anyone. In addition to authenticating, some APIs require you to submit an application to get a key, and some require you to pay for access to their API. The DPLA API is free and open to the public, so you can get a key by just sending an email to them.

Storing API Keys

Copy the key from the email and we are going to store in a new Python script. Create a new folder in is310-coding-assignments called api-getting-data and then create a new script called first_api_script.py and import requests into the script. Then save your key into a new variable called api_key.

import requests

api_key = "YOUR_API_KEY_HERE"

While this is an easy way to store your API key, it’s not the most secure. For example, if you pushed this up to GitHub, then everyone would be able to see and use your API key. Since the DPLA API is free to use this isn’t a huge issue, but imagine you’re using an API that you have to pay for access to. If that was the case someone could easily use your key and you would be charged for their usage. Furthermore, if you’re working with sensitive data, you could be putting that data at risk. Additionally, if someone is authenticated to your key and tries to request more data than you are allowed, you could be locked out of the API. Even worse, if they do something illegal with your key, you could be held responsible. So rule of thumb is don’t share your API key!

There are a number of ways to more securely store your API keys.

One option is just copying our API keys to a text file and save them there (especially because they are rarely something you can memorize), but there’s also more programmatic ways to do this.

Another option is that you could store your API keys as an environment variable. Environment variables are a way to store data that is accessible to all programs running on your computer.

To create an environment variable, you open your terminal and type the following, replacing api_key with your API key.

For Macs/WSL:

export DPLA_API_KEY="YOUR_API_KEY_HERE"

For Windows/Powershell:

setx DPLA_API_KEY "YOUR_API_KEY_HERE"

Now you can access these environment variables in your Python script by using the os library.

import os

dpla_api_key = os.environ['DPLA_API_KEY']

print(dpla_api_key)

However, these will only be available in the terminal you created them in, so you would have to create them every time you open a new terminal. If you want to make them available in every terminal, you can add them to your .bashrc or .zshrc file on Macs/WSL or your profile.ps1 file on Windows.

This is a bit more work though, and one easier option is to use a Python library for storing API keys, called apikey https://github.com/ulf1/apikey.

You simply download the library with pip install "apikey>=0.2.4 and import it. Then write:

import apikey

apikey.save("dpla_key", "YOUR_API_KEY_HERE")

dpla_api_key = apikey.load("dpla_key")

While you can use any of these options, I would recommend using the apikey library, as it’s the most secure and the easiest to use. If you continue with programming, you will likely end up using the .zshrc or .bashrc method, but for now, the apikey library is the best option.

Making a Request to DPLA

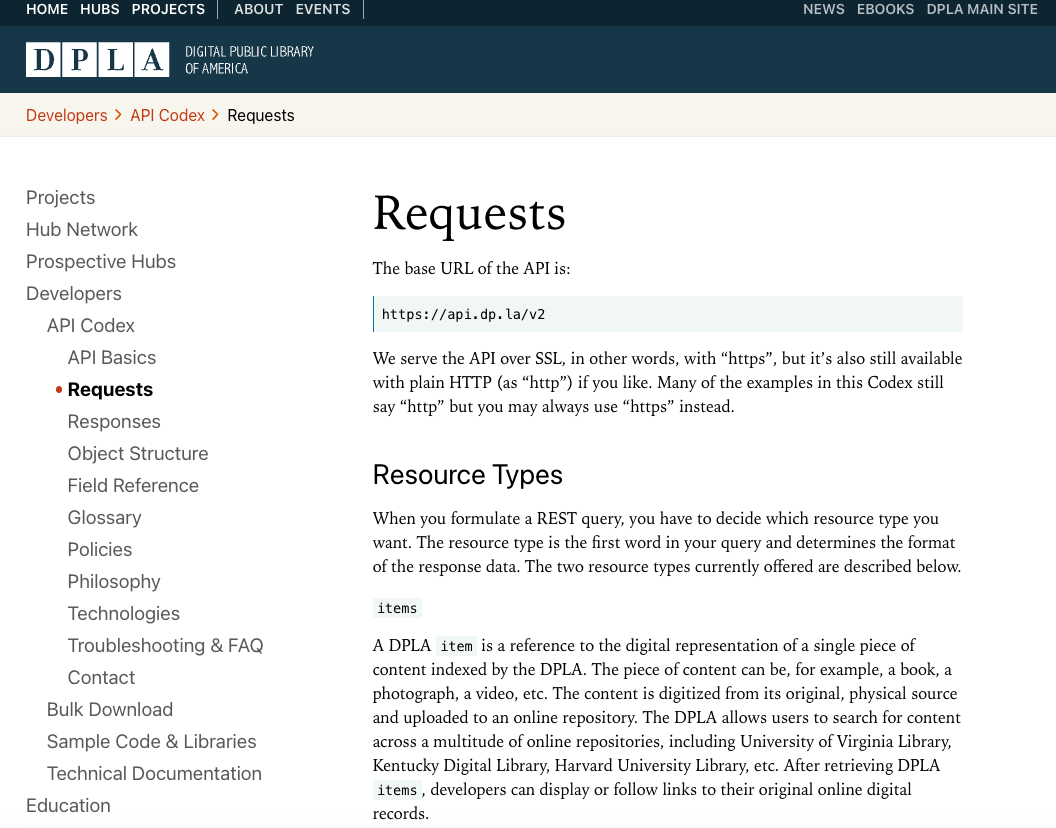

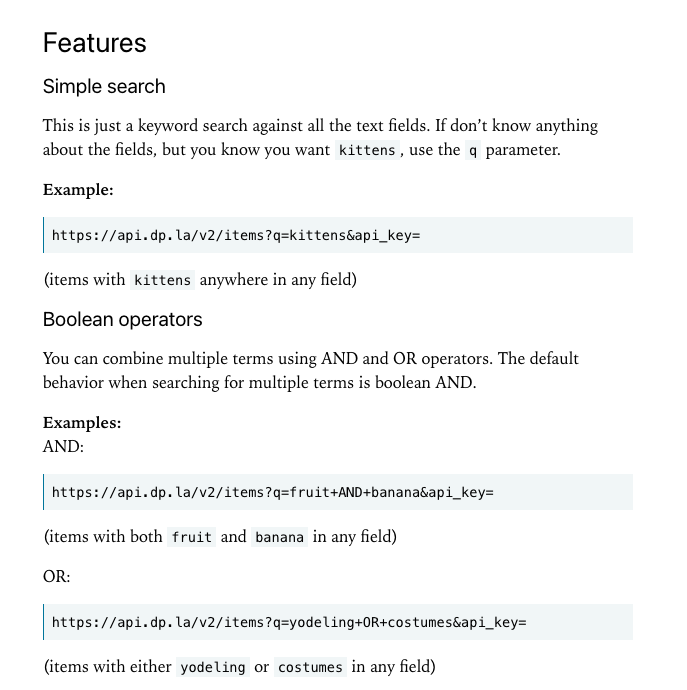

Now that we are fully authenticated, we can start making requests to the DPLA API. To figure out how, we can look at the DPLA API documentation to see how we can start getting data from their databases https://pro.dp.la/developers/requests.

Let’s start with the simple search example https://pro.dp.la/developers/requests#simple.

Copy their example url into your script and save it as the variable url. Then try to get the data from the API using the requests.get method we’ve used previously.

import requests

import apikey

dpla_api_key = apikey.load("dpla_key")

url = 'https://api.dp.la/v2/items?q=kittens&api_key='

response = requests.get(url + dpla_api_key)

Notice that the end of the url variable is api_key= and that in the requests.get, we are concatenating url and api_key. That’s how we pass our key to the DPLA API so that it knows who we are and that we are allowed to use their API.

Let’s try to print out the status code.

response.status_code

What does 200 mean again? If you’re unsure, feel free to return to our intro to web lesson and look at the status codes section.

How could we see what data got returned from the API? We could use two methods, either .text or .json() Let’s try to print out the response, using the json one.

response.json()

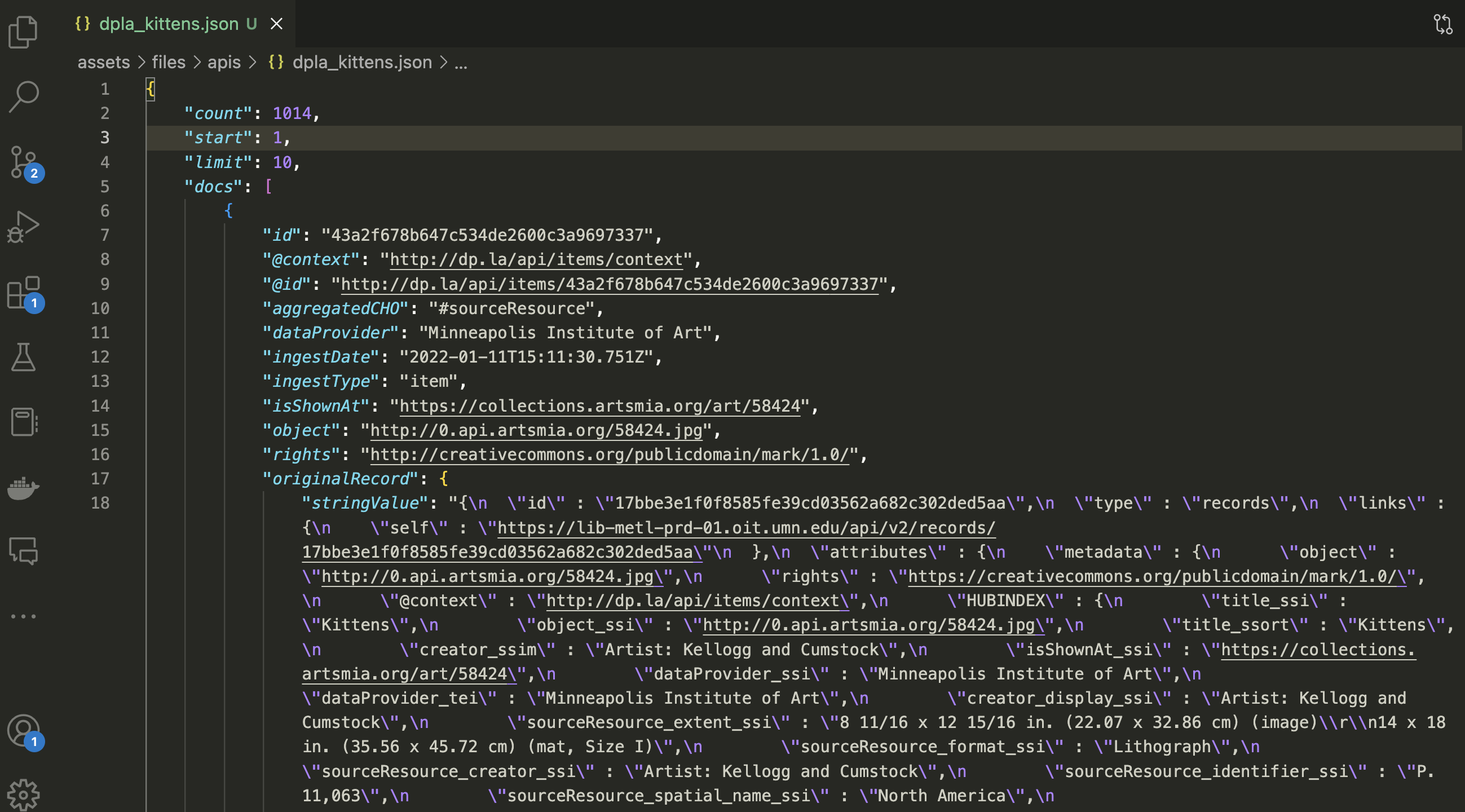

You should see something like the following, though it should be much longer:

{"count": 1014,"start": 1,"limit": 10,"docs": [{"id": "43a2f678b647c534de2600c3a9697337","@context": "http://dp.la/api/items/context","@id": "http://dp.la/api/items/43a2f678b647c534de2600c3a9697337","aggregatedCHO": "#sourceResource","dataProvider": "Minneapolis Institute of Art","ingestDate": "2022-01-11T15:11:30.751Z","ingestType": "item","isShownAt": "https://collections.artsmia.org/art/58424","object": "http://0.api.artsmia.org/58424.jpg","rights": "http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/","originalRecord":

This is the data that the DPLA API returned to us. It’s in a format called JSON, which stands for JavaScript Object Notation (Sometimes it’s pronounced “Jay Song”, but it’s really “Jason”) and was originally designed to allow websites to pass data back and forth between the browser and the server. But it’s become a really popular generic format for all sorts of things and all sorts of languages.

First, we can also store it as a json file, so that we can look at it later.

import json

with open('dpla_kittens.json', 'w') as f:

json.dump(response.json(), f)

Here we are using the JSON module for Python and in particular using the json.dump method to write the data to a file called dpla_kittens.json. We are using the w argument to tell Python that we want to write to the file. If the file already exists, it will be overwritten. If you want to add to the file, you can use the a argument, which stands for append.

You’ll notice looking at the file that it has a somewhat similar structure to a Python dictionary. In fact, it’s a way to store data that is similar to a Python dictionary. We can use the json method to convert this data into a Python dictionary.

dpla_data = response.json()

Now let’s try to print out just the keys of the dictionary.

print(dpla_data.keys())

You should see the following list of keys:

dict_keys(['count', 'start', 'limit', 'docs', 'facets'])

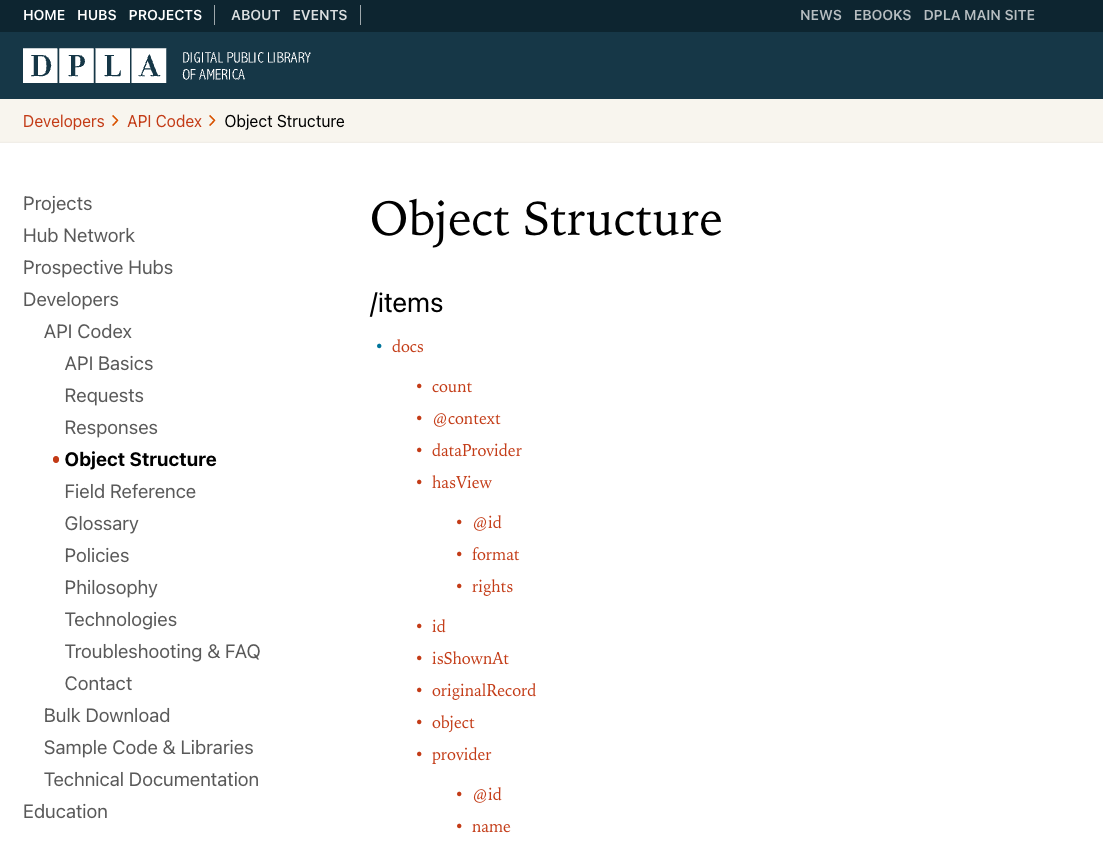

These aren’t that meaningful to us, but we can start to investigate what they mean by looking at the API documentation https://pro.dp.la/developers/object-structure.

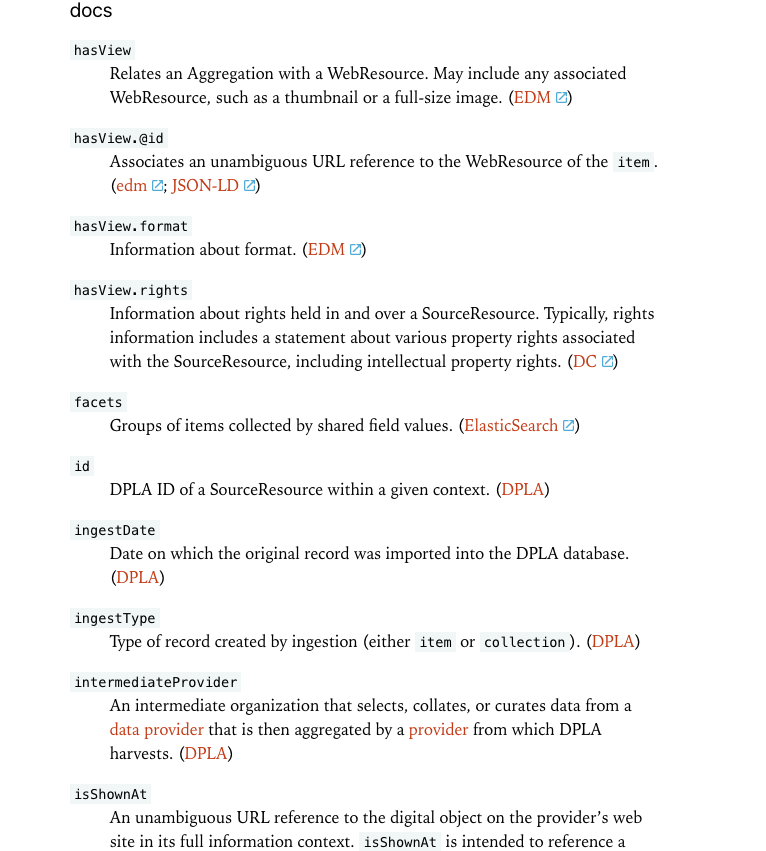

This documentation is pretty sparse, so let’s click on the docs option https://pro.dp.la/developers/field-reference#docs.

Now we can see the data that corresponds to all the fields that we see in our response.json() object.

A lot of these fields are still pretty dense, so let’s take a look at one of our items. Try printing out the following code in your script:

print('dataProvider', dpla_data['docs'][0]['dataProvider'])

print('isShownAt', dpla_data['docs'][0]['isShownAt'])

print('sourceResource', dpla_data['docs'][0]['sourceResource'])

In this code, I’ve selected one of the keys from dpla_data (docs in this case), then indexed the first item since the value of docs is a list, and then because that list contains dictionaries, I then pass in some keys to look more closely at this data. This should print out the following:

'Minneapolis Institute of Art'

'https://collections.artsmia.org/art/58424'

{

'@id': 'http://dp.la/api/items/43a2f678b647c534de2600c3a9697337#SourceResource',

'creator': ['Artist: Kellogg and Cumstock'],

'date': [{'displayDate': '19th century'}],

'extent': ['8 11/16 x 12 15/16 in. (22.07 x 32.86 cm) (image) 14 x 18 in. (35.56 x 45.72 cm) (mat, Size I)'],

'format': ['Lithograph'],

'spatial': [{'name': 'North America', 'coordinates': '46.07323, -100.54688'}],

'title': ['Kittens']

}

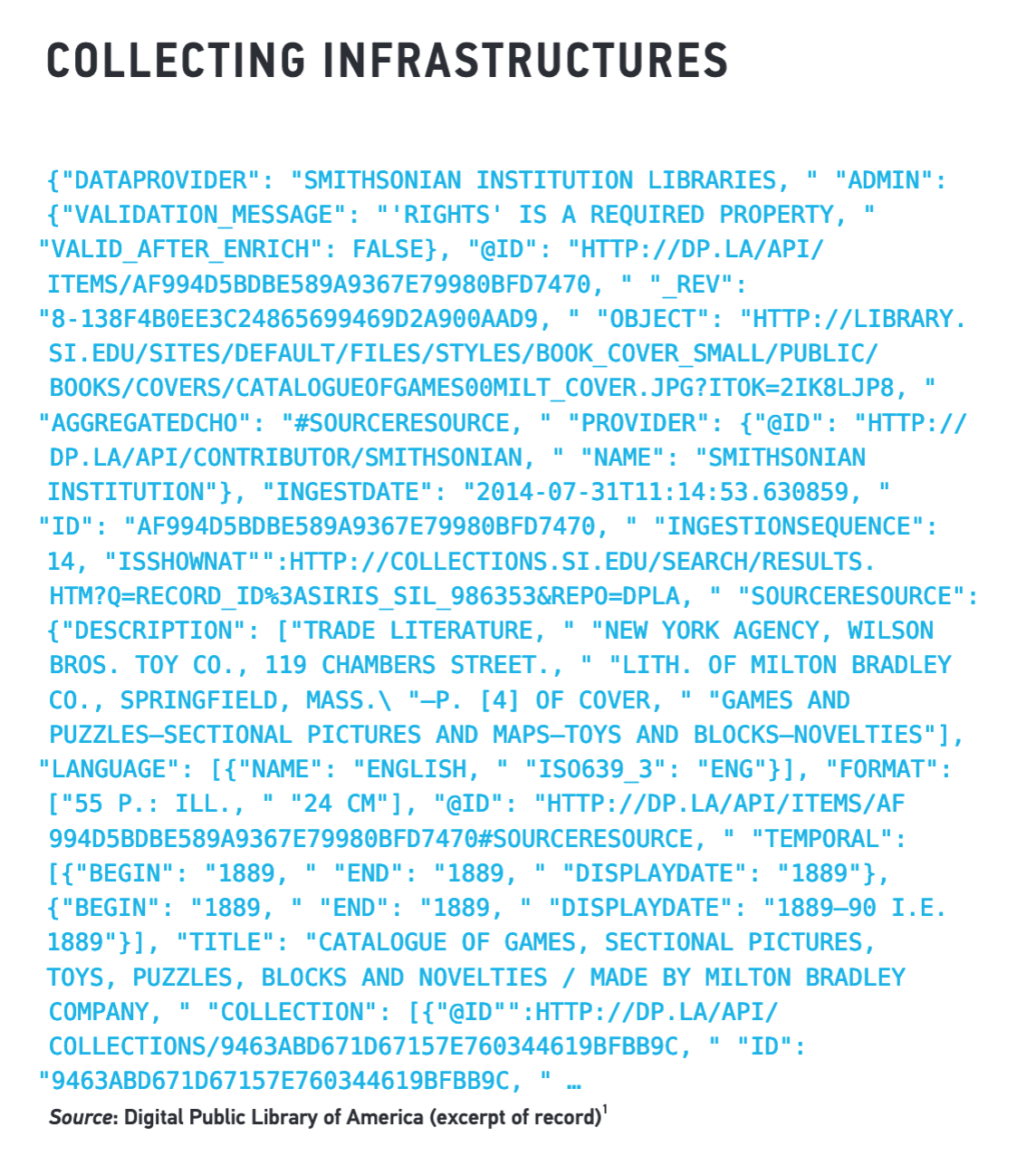

To help us understand what we are looking at, let’s look at the image that corresponds to this data from All Data Are Local.

We can see that our API response is similar to what was printed at the front of the chapter that we read.

It might be hard to tell from this image, but one of the fields has a jpg file as value. So let’s also look at the object field in the data we received from the API.

print('object', dpla_data['docs'][0]['object'])

If we click on this link, we should see the following image of the kittens.

This helps us get a sense of what the data is describing. We can see that the data is describing a piece of art from the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The title of the piece is Kittens and it was created in the 19th century. We also have a link to the image of the piece of art.

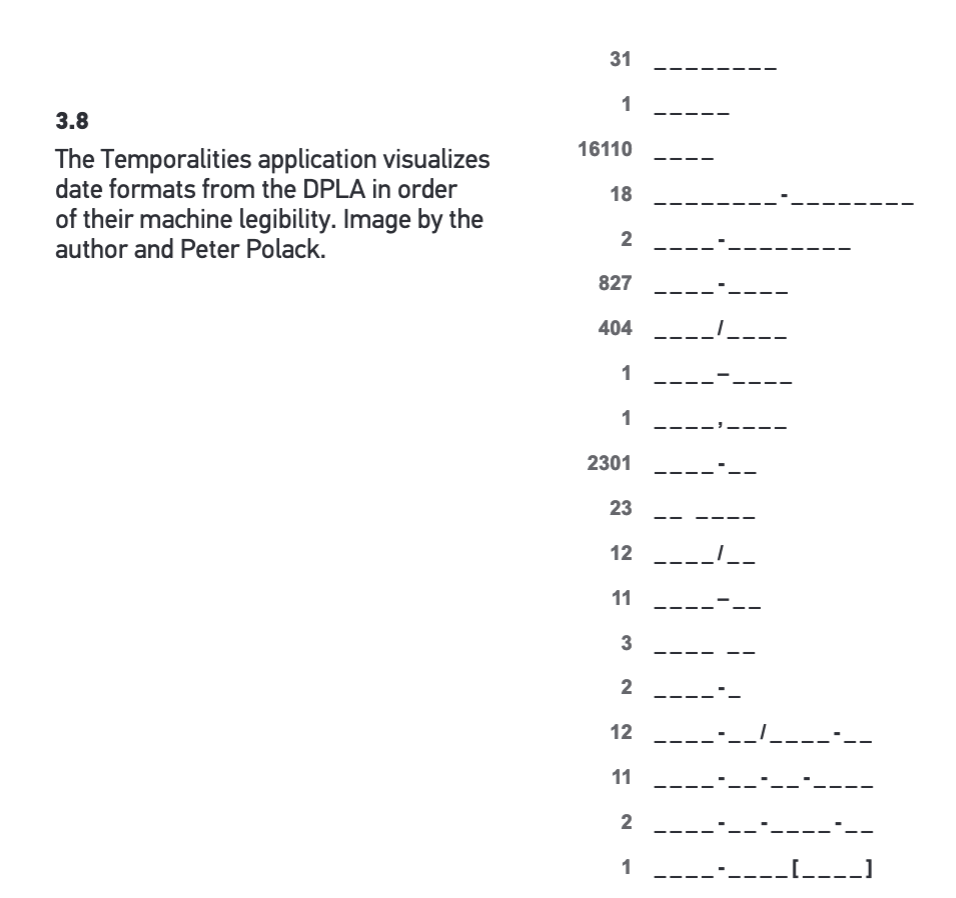

Returning to All Data Are Local, part of the chapter was showing two projects that were built using the DPLA API:

Both of these projects were designed to show how messy the data in the DPLA API is because it is reconciling metadata from multiple digital libraries. How would we find the origin of the data and the temporal context of the data?

DPyLA

While we have been using requests to get this data, there’s also the DPyLA library, which is a wrapper library optimized to work with the DPLA API. Many popular APIs have wrapper libraries, for example to work with the Spotify API, you could use the spotipy library https://spotipy.readthedocs.io/en/2.22.1/. Wrapper libraries can be useful because they already document the API and provide methods to make requests to the API.

You can find the documentation for the library at this link https://github.com/bibliotechy/DPyLA (notice it was last updated 2 years ago). To install the library, you just need to activate your virtual environment (if you forget how, see the instructions here) and then once it is activated, you can install the library with pip3 install dpyla.

Once it is installed, we can import the library and make a request to the API.

from dpla.api import DPLA

dpla = DPLA('your-api-key-here')

# Now make your search

response = dpla.search(q="kittens")

print(response.items[0])

With that print statement you should see the same thing we explored above, just without having to use requests. The options are essentially equivalent, but it’s helpful to use requests since many wrapper libraries like DPyLA are updated less frequently than the API itself and may also not provide the full ability to query the API.

Quick Exercise

Try replicating your work with the DPLA API using the DPyLA library. Notice any differences? Which do you prefer?

APIs in the Wild Assignment

So far we have just been working with the DPLA API, but there are many other APIs out there. For your homework, you will research and select new APIs to work with. You can select any API you want, using either a wrapper library or the requests library, and if you need inspiration, you can look at the following resources:

- https://github.com/chanonroy/cool-apis

- https://github.com/public-apis/public-apis

- https://apilist.fun/

- One of my personal favorites is SWAPI (the Star Wars API) https://swapi.dev/documentation

After you pick an API, read through the documentation and find a way to get data from it. For APIs that require authentication, make sure you authenticate and store your API keys locally.

Once you have the data, subset the data so that you only have one item, print out the entirety of that item in your script, and then store it either as a JSON file or as a CSV file (choice is yours) with the filename that includes the API you selected.

Finally, push both your script and the data to your Github repository. You can name your script whatever you like but it should be in your api-getting-data folder and the data should be in a new folder called data in your api-getting-data folder. Share the link to your repository in the GitHub discussion for this assignment.https://github.com/ZoeLeBlanc/is310-computing-humanities-2024/discussions/5

Resources

- Go Sugimoto, “Introduction to Populating a Website with API Data,” Programming Historian 8 (2019), https://doi.org/10.46430/phen0086.

- Patrick Smyth, “Creating Web APIs with Python and Flask,” Programming Historian 7 (2018), https://doi.org/10.46430/phen0072.