Programming Over Projects: Teaching Machine Learning for Humanities at an iSchool

For DH2024, I was very lucky to be asked to join a workshop on Teaching Machine Learning for Humanists, and while I’m not sure I’ll make it on time (currently waiting to see if my 6am flight will be delayed), I wanted to share my slides and notes here.

Workshop Description

The workshop was organized by Natalia Ermolaev and Andrew Janco, and I’m scheduled to give talks with Toma Tasovac, Melanie Walsh, Quinn Dombrowski, William Mattingly, Mia Ridge, Nathan Kelber, and Kahyun Choi. For background, this is the summary of the workshop:

In recent years, advancements in machine learning (ML) have opened exciting new capabilities for the computational humanities, giving rise to new pedagogical initiatives to teach applied ML specifically in a DH context.

This workshop will meet at DH2024: Reinvention and Responsibility to share experiences, best practices, and strategies for teaching ML—its techniques, potentials, and risks—to the humanities community.

The presenters and participants of this workshop teach (or plan to teach) ML to humanists at multiple levels—undergraduates, graduate students, as well as faculty and advanced researchers—and in various modalities—in-person, hybrid, and asynchronous.

Attendance is open to any technologist, researcher, librarian or student interested in either refining their methodology of teaching ML in the humanities context, or is curious to embark on teaching ML to humanists.

And here’s a fun photo from the WHOVA app for promoting the workshop:

Programming over Projects

Here’s the text of my talk, I’ll update with the slides and video when I can and you can find links to all my syllabi on my teaching page.

Hi everyone! I’m thrilled to be part of this workshop, and want to start by thanking both the workshop and conference organizers for all their hard work 👏🏽!

For those I haven’t met before, I’m Zoe LeBlanc and I’m an Assistant Professor at the School of Information Sciences at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. My research focuses on histories of information and digital humanities, and I also teach many of the DH courses at the iSchool.

Today, I’m excited to share my experiences teaching machine learning, particularly for students who, even though they’re in an iSchool, have a strong interest in humanities research and are eager to explore how these methods can enhance their work.

Since I only have seven minutes, I’ll be focusing on two courses that I’ve developed. The first course is aimed at advanced iSchool graduate students, though it also attracts doctoral students from other departments (mainly Media & Cinema Studies so far), as well as some advanced MSLIS students. The second course is part of our relatively new undergraduate program. Unlike most humanities departments, our iSchool only launched its undergraduate program about four years ago, so we’re still figuring out how to best teach these methods to students who are new to the field.

Culture At Scale

The first course I’m going to talk about is called Culture at Scale. The title might sound a bit unusual, but I wanted to capture the essence of how scale and computational methods can help us study culture. This course is something I had been dreaming about for years––honestly, ever since I was a PhD student––so I was very excited to finally put it together, and I’ve taught it twice now.

Culture at Scale is a unique course, I would wager, in DH (or at least American DH). Unlike many DH courses that serve as an introduction to programming, this is not an entry-level course. Instead, it’s intended for students who have already completed at least two or three courses that are quite intensive in programming and statistics, sometimes even more. For example, last semester, many of the students had taken an advanced graduate seminar on LLMs. This means that for this group of students, knowing how to code is usually not the issue and they are generally aware of at least some advanced computational methods.

This course is also a bit unique in that given my iSchool has a longstanding investment in the Humanities, unlike some other institutions. So, many of these students already have a deep interest in humanities research, often coming from backgrounds in English, History, Art, etc. This means that I’m not hampered by the usual obstacles to DH teaching, such as a lack of programming knowledge or an understanding of what constitutes an interesting humanities research question.

But even with this structural support, I’ll be frank that this course has been challenging to teach, since its focus goes far beyond any one discipline (my Zotero library for the course is massive!).

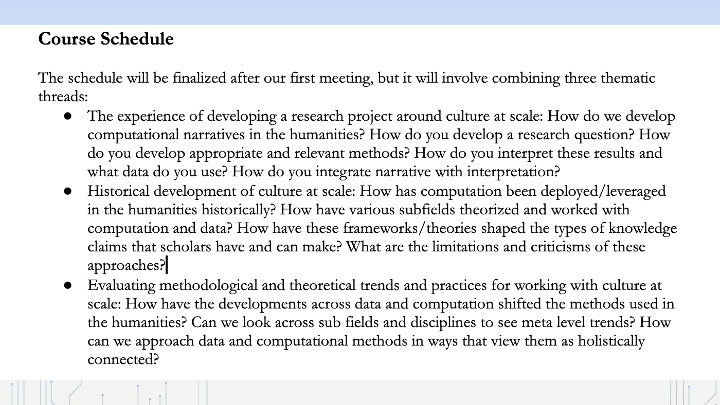

To help manage this, I’ve broken the course into three themes:

The first theme is the experience of conducting a research project centered on Culture at Scale, which is the core assignment but also one of the discussion themes of the course. Essentially, digging into how we do this work. We explore what sorts of research questions are amenable to this type of work and how we interpret the results, as well as discussing the various stages of this type of work (from struggling to find data to struggling to get it correctly formatted to struggling to interpret it––lots of struggles!). The goal is to help students navigate a hands-on experience of applying computational methods to cultural data.

The second theme is the historical development of Culture at Scale. We examine how computation has historically been used to study humanities questions. This includes looking at how different fields and disciplines have approached this work, as well as the criticisms that have emerged both from within and outside these fields. This historical perspective helps students understand the evolution and the interdisciplinary nature of computational humanities.

The third theme focuses on evaluating the methodological and theoretical trends in working with Culture at Scale. We assess the state-of-the-art practices and consider whether we can view these diverse practices holistically, despite their origins in different computational fields and disciplines. This theme encourages students to critically engage with current methodologies and to think about the theoretical implications of their work.

ML & Culture At Scale

When it comes to machine learning specifically, I have two main goals in the course.

The first goal is to situate machine learning within a broader computational context. This means viewing machine learning as part of a continuum that includes descriptive exploratory statistics, network science, and the often-discussed divide between unsupervised and supervised learning, to name but a few methods that we discuss. I want students to see these methods as interconnected approaches to working with cultural data, rather than isolated techniques. This holistic view is crucial because in DH, there is a tendency to adopt methods based on their historical popularity rather than their suitability for specific research questions.1 In the course, students must justify their choice of methods, arguing why one approach is better suited to their research than another, but also consider how working with texts or images or other forms of data often can benefit from a combination of similar methods.

The second goal is to critically examine what constitutes best practices in this evolving field. Much of our work in DH draws on practices from other fields that have different assumptions about data and its representation. For instance, how we handle missing data can differ significantly from other disciplines. We need to develop best practices that are informed by humanistic concerns. This means placing less emphasis on memorizing equations or chasing the latest state-of-the-art technique for its own sake. Instead, we focus on what it means to report metrics like F1 scores or resample when dealing with historical data. We also emphasize the importance of experimenting with hyper-parameters and validation measurements to understand the stability of the models and methods we use for our research questions.

Ultimately, there is a significant debate in DH regarding the role of computation. I try to be fairly agnostic on this debate, but in the course I do try to encourage students to explore computation holistically, from ‘stirring the archive’ to modeling it. My hope is that this helps them think critically about how and where they want to utilize computation to further their knowledge claims.

Computing and the Humanities/Culture as Data

Part of what makes Culture At Scale doable is that there’s a strong emphasis on project-based learning (students propose a project and work on it over the course of the semester), which is something that I’ve also integrated into my undergraduate course Computing in the Humanities.

Now I want to emphasize that I know I’m incredibly lucky to have classes small enough to make project-based learning feasible. I also know that this is not the case for many DH courses, especially at the undergraduate level. But I do think that project-based learning is crucial for teaching machine learning in the humanities. It’s not enough to just learn the theory or the methods; students need to apply these methods to real-world problems to understand their strengths and limitations.

This is especially challenging with undergraduates in our program since almost none of them have any humanities experience. In fact, most are so unfamiliar with the term that I’m trying to get the course renamed to Culture as Data to better reflect the content. The focus of the course is on understanding how and why we represent culture as data, helping students understand that data, rather than being a given, is actually constructed.

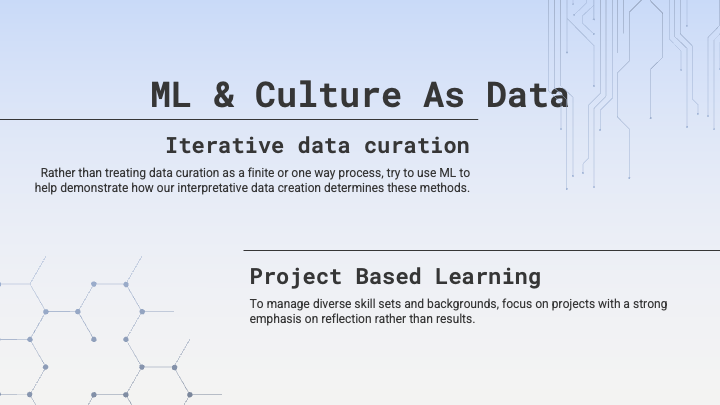

ML & Computing in the Humanities

A key component of this course is understanding data curation holistically. Students are tasked with creating data in some way—––either by finding and combining existing datasets or creating new ones from scratch. One of the difficulties in creating data is that students often don’t understand the impacts of their choices until they actually use the data. To address this, I introduce them to basic clustering through topic modeling, classification through TF-IDF and Logistic Regression, as well as the general principles of text analysis. We also touch on network analysis to help them see how their data representation choices determine the utility of these methods. While I’m definitely covering a lot in this course, I do think including these methods is crucial to helping students understand how they open up new ways of interpreting cultural data, even if the students don’t have much of a sense of what makes a good research question or not.

This is also where project-based learning is crucial since students in the course often have a diverse background when it comes to programming and computational methods, so working on a project allows them to experiment without having the pressure to produce a perfect result. This is especially important when it comes to machine learning, where the results can be quite unstable and the methods can be quite opaque.

Similar to Culture at Scale, machine learning is not the central focus of the course. We don’t spend a lot of time optimizing models; instead, we try out different methods, test hyper-parameters and assess the stability of the results, and finally explore how the methods and data affect the outcomes. In essence, I try to approach machine learning as an applied method for humanities research. This means that students need to understand the assumptions built into these methods and how they affect the results. This is a significant shift from how machine learning is often taught, where the focus is on the technical aspects of the method rather than the interpretation of the results.

Trade-offs and Takeaways

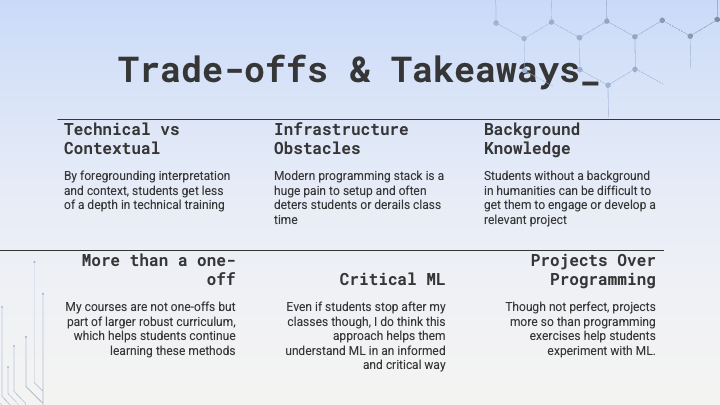

To sum up, I’d like to discuss some of the trade-offs, takeaways, struggles, and successes I’ve experienced. As you can tell, I prioritize a contextual understanding of machine learning—how we interpret the results—over a purely technical understanding. It’s important for students to grasp the assumptions built into these methods, but I’m more concerned with helping them see the applicability of these methods to studying culture.

There are significant trade-offs though, especially in getting students up and running with the necessary technical infrastructure. Many students struggle with installing libraries, setting up virtual environments, and understanding the larger coding infrastructure. Moreover, students without a humanities background often find it challenging to determine what makes interesting results using machine learning. I try to manage this through project-based learning, but it remains a struggle.

One of the successes is that this approach benefits from a robust curriculum, which is rare for DH courses that tend to be one-offs. Instead, this is not the only course where students encounter machine learning. We have courses specifically focused on machine learning; though those often treat data as a case study for the method, whereas my course inverts this relationship. This allows students to see the potential value of this work and decide if they want to pursue it further. Even if they choose not to, they gain the ability to critically evaluate machine learning and understand both its strengths and limitations.

In my courses, I foreground interpretation rather than methods. Such an approach is far from perfect, but I think it provides an important contrast with how CS typically handles these topics and, I believe, provides a valuable and necessary perspective for students. Ultimately, I think my approach can be summarized as prioritizing projects over programming. Despite my love for programming (including ML), I’ve found that this project-based focus is the most effective for students looking to understand how computation can help us study culture.

Thanks for listening, and I’m happy to take any questions!

-

I’m not trying to call anyone out here, but do think there’s some deep structural issues in American DH that prevents us from thinking critically about the methods we use. I’m happy to talk more about this in the Q&A or come to my panel on Cultural Analytics Research and Teaching Friday morning! ↩

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: