Depictions of Decolonization SHAFR 2017

For SHAFR 2016, I co-organized with Micki Kaufman the first digital history panel at the conference. Our panel was a lot of fun, and we published abbreviated versions of our talks in SHAFR’s newsletter Passport.

This past year (2017), I wasn’t sure I was going to travel to SHAFR but I was asked to join another digital history panel, and agreed to present some preliminary research avenues. The panel was titled, “Doing Digital History”, and Micki and I both presented again with Marc Selverstone providing excellent commentary.

I don’t usually post my conference talks, but I wanted to share this one for other scholars who might be interested in using digital image analysis in their studies of public diplomacy.

Depictions of Decolonization: Cairo, Anti-Colonialism, and Digital Image Analysis

Good afternoon everyone. Before I get started I want to thank Marc for agreeing to chair this panel and to Micki for helping bring this panel together. Last year we had a great discussion at our “Doing Digital Diplomatic History” panel at SHAFR and I’m excited to continue that conversation today.

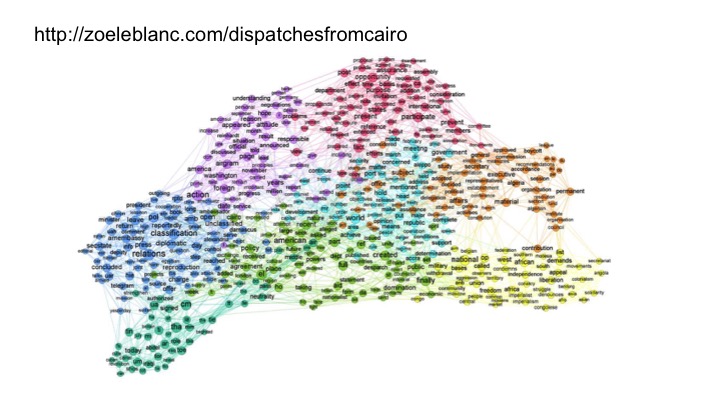

Last June, I presented on using digital history to analyze diplomatic dispatches from the American embassy in Cairo in the 1950s and 60s. I’m still working on that part of my research, but today I’m shifting gears away from textual sources towards print images. One of the most frustrating aspects of current text analysis methods is that as part of the data cleaning process you often remove the images from the document. While this approach is fine for a study of hundreds of novels, for historical magazines and newspapers this method throws out some of the most interesting historical evidence. So today, I want to share how I’ve worked to integrate images into my digital history methods and research, and hopefully provide some insight into these new research directions for historians interested in studying images in foreign relations.

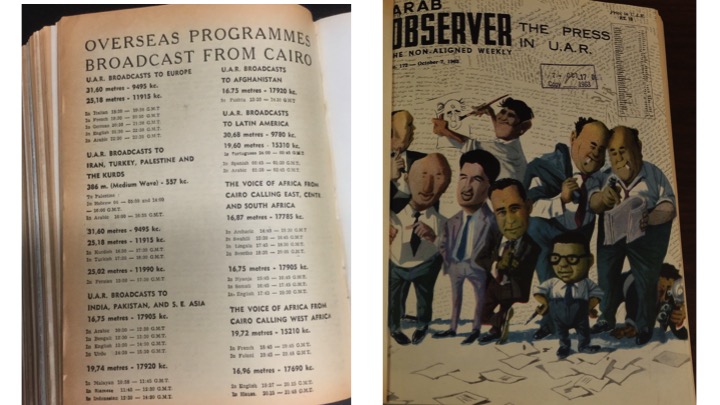

So for some background, my dissertation explores Cairo in the 1950s and 60s as a hub for international anti-colonial media production. I trace how Cairo, more so than any other Third World capital, sought to leverage various medias to construct international anti-colonial solidarities. One of the more famous efforts was Radio Cairo, which was broadcast across the continent in multiple languages. And in this slide you can see their broadcast schedule from the summer of 1964.

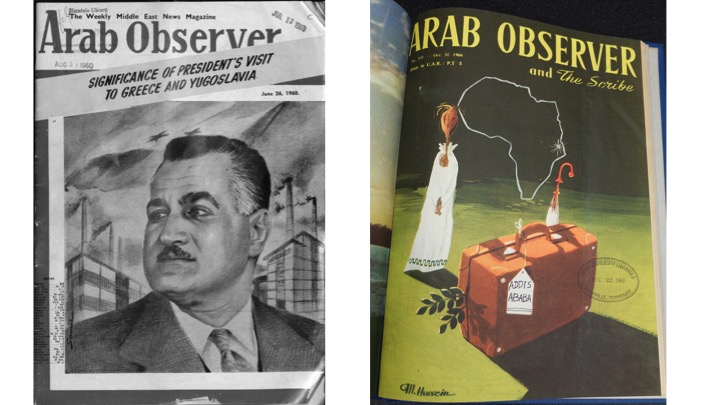

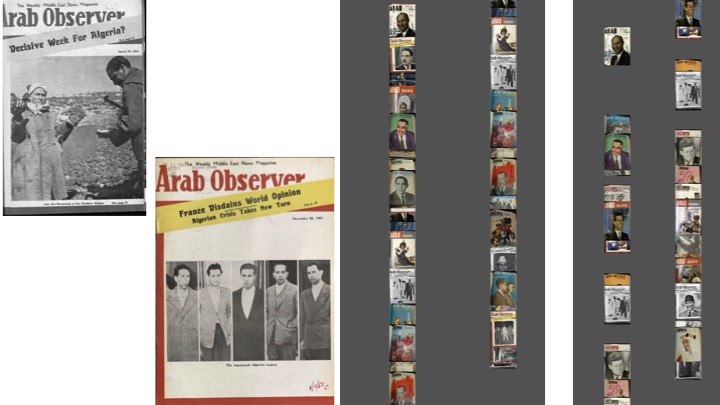

The other arena where Cairo was pre-eminent was as a publication hub with the government funding numerous newspapers and magazines, as well as offering anti-colonial activists from other countries resources to print materials, all of which circulated across the anti-colonial world. In my research, I explore these sources, as well as newspapers from other Third World capitals to understand how the meanings of anti-colonialism shifted over this period. The other image in this slide is from one of these magazines, The Arab Observer, which is the publication I’m focusing on today, and I think this image is great representation of my dissertation.

So obviously many diplomatic historians have already studied imagery and foreign relations whether through the lens of culture and diplomatic history, or more recently in studies of public diplomacy and propaganda. While there are large literatures on this subject, I want to mention two recently published books: Sonke Kunkel’s Empire of Pictures *and Jason Parker’s *Heart, Minds, Voices. Empire of Pictures explores the “global flood of images” that emerged in the 1960s, focusing particularly on the use of images in constructing American empire and power abroad. And a lot of my thinking on this subject draws heavily from Kunkel’s methodology, and especially his emphasis on pictures as historical actors. Parker’s *Heart, Minds, Voices *also provides an excellent overview of USIA attempts to counter Third World public diplomacy and to shift international public opinion. Both of these works underscore the importance of media as a political battleground, but the lens of public diplomacy really hasn’t fully been utilized in studies of non-Western foreign relations. So I’m trying bridge these studies of public diplomacies with literatures on non-Western media cultures.

The United Arab Republic under Gamal Abdel Nasser is a particularly interesting case study since most of the media was either state owned or censored. Thus, many of these publications offer a window into the Egyptian state’s prescriptive vision of anti-colonialism, especially in the absence of open government archives.

I first became interested in the symbolism of anti-colonialism in my research on the response to the Congo Crisis in Cairo. While most of my research involved diplomatic cables and speeches at the United Nations, I was surprised to keep finding pictures of Patrice Lumumba’s widow and children in various Egyptian newspapers and magazines in the early 1960s. I started wondering how these types of pictures were used to symbolize the UAR’s vision for anti-colonial solidarities.

A more famous image of these anti-colonial solidarities is this image of Nasser, Nehru, and Tito from the Brioni meeting in July 1956, which many mark as the beginning of the non-aligned movement. These types of pictures often become book covers, but what about their role in shaping this history?

For a quick tongue and cheek answer, one just has to check Twitter to see what has now become a genre of images of Trump being compared to Obama in what are generally termed ‘photo-ops’. As a Canadian, I chose these two, and in many ways these images speak for themselves. Yet, I also want to share these images as a way to consider the ways in which pictures can define political narratives and moments.

But today I also want us to consider this same question but with a thousand or tens of thousands of these images. This proposition might feel overwhelming or exciting depending on your perspective, but regardless this hypothetical is increasingly becoming a reality. So how should diplomatic historians proceed?

The answer to that question is one that no historian along can provide, but today I’ll try and discuss some of these exciting new research avenues, along with some of the frustrations and ethical grey areas of deploying computer vision.

The first step in any digital history project is getting your data. This activity is activity is critical to any digital history project, and most of the existing research on computer vision relies on either born digital images from social media or from previously digitized corpuses, like the Chronicling America project from the Library of Congress. For most historians, these two categories cover a lot of temporal ground. However, for modern historians we’re stuck between copyright law that’s slowly inching up the 1920s and digital archives that really only emerged in the late 1990s. This reality means that there’s limited existing publicly available datasets for the mid-twentieth century. One of the biggest struggles in my research has been finding efficient ways to create my own image collections. However, relying on previously created datasets isn’t without its own pitfalls. For historians, collecting archival sources is as much a part of our research as writing, and this reality remains true even if you’re working with digital images.

Some existing image management tools include flickr, photo libraries, DevonThink, and various cloud storage offerings. Most of these offerings provide limited means to transform images. This past May, the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University released Tropy (NOTE: https://tropy.org/), which is probably the best photo management tool I’ve come across. If Tropy had been available earlier, I might have used it more in my research. But instead like the ambitious grad student I am, I actually built my own application that I’m calling Image Lucida to be my dream research collection platform. That being said, a lot of what I do with Image Lucida can be achieved with freely available sources.

My process involves uploading my archival images, organizing them into the relevant folders and adding meta-data, like publication issue, page number, and tags. One of the most difficult steps in this process beyond building the application is creating a standardized ontology for organizing and tagging these images. This cleaning and curation of these sources is the most time consuming, but I believe is a critical step in the research process. Afterall, a different historian interested in different questions might tag certain images differently or organizing images in different hierarchies.

Also before I go into how I’ve used digital image analysis in my research, I first want to explain a bit about how computers understand images. Images, regardless of file type, are actually a set of pixels which can be read by a machine as a series of numbers, usually in a matrix. Most digital image analysis can be divided into three categories: the use of human tagging of images to identify features, analyzing meta-data that was either entered by humans or generated from image files, and lastly computer vision libraries and proprietary databases that are used to analyze pixels and extract image features. Now there’s a lot of overlap between these categories, but a helpful distinction between these methods is whether a method uses human interpretation as a basis for analysis or computed statistics of pixel groupings.

After adding the metadata, I utilize a combination of OCR and computer vision resources. The two main ways I use computer vision is to clean my data and analyze it.

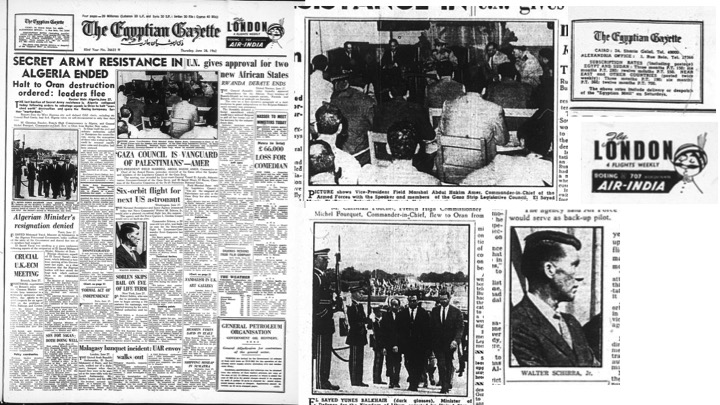

So for images that I’ve uploaded, I first extract any text using either the Tesseract or Google Vision APIs. Then If the source does have images, I run it through a computer vision algorithm, called Otsu thresholding, that automatically removes the images. This slide is an example of what the algorithm produces from a cover of The Egyptian Gazette. So as you can see it’s fairly accurate though newspapers are particularly difficult for computer vision algorithms because they are so busy.

For today, I’ve processed a number of the issues from The Arab Observer: The Non-Aligned Weekly, which was a state-funded periodical published in Cairo from 1960-1966. Over the course of this period, The Arab Observer circulated throughout anti-colonial, leftist, and revolutionary networks. Full disclosure, what I’m presenting today is fairly preliminary analysis, but I’ll also talk a bit about where I hope to take this research.

The first cover here is the first issue of The Arab Observer that I’ve found from June 26 1960 and the second cover is the last issue of the Arab Observer that I have from October 31, 1966. I have almost 300 issues of the magazine in my collection, though I have found catalogues listing the publication up until 1975.

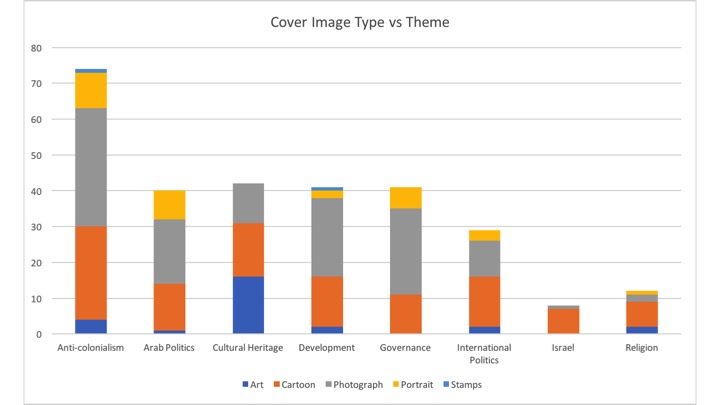

Using a combination of tagging, pixel analysis, and the Google Vision API, I have annotated these covers to try and get a sense of how their symbolism changes over this time period.

The first question I wanted to explore is which places appeared more often in the covers. Overwhelmingly Cairo is the location for the covers, though towards the end of this period the covers became increasingly abstract and thus they did not have a geographic location. Also for some reason this map represents null values as California, which I left as an interesting question.

As you would assume, Gamal Abdel Nasser appears frequently on the cover (approx. 28 times). Though the range of subjects varies a great deal. One of my favorite series is looking at the covers from around July 23, which is the anniversary of the Free Officer’s Revolution.

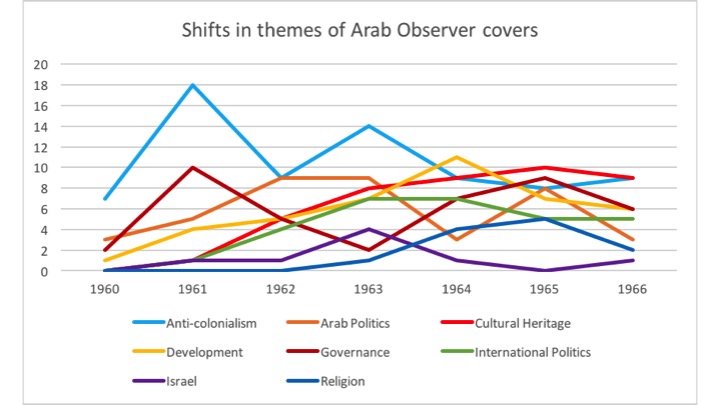

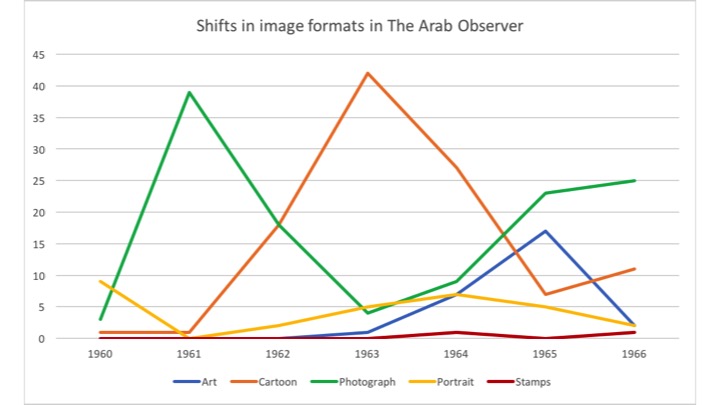

While I have tried to extract places and people from these images, I have also been interested in how the themes and formats of the covers change over time. As you can see in this slide, Anti-colonialism was initially the overwhelming focus of the magazine, but over this period you can see a shift in coverage towards development and what I’ve termed cultural heritage.

This shift is also reflected in the format of the covers. For anti-colonial covers, initially the covers utilized photographs of leaders, but starting in 1962 the magazine started to depict leaders with hand drawn portraits. This continued until about 1965 when the magazine started depicting more abstract covers, with the name becoming The Arab Observer and the Scribe. I argue that this shift towards a more literary and cultural heritage focus for the magazine, coincided with a shift in the tenor of anti-colonial politics in Cairo.

While the magazine still featured some coverage of anti-colonial leaders and conferences in Cairo, it no longer depicted political events through radical cartoons or strident headlines. While this change may be in part due to changing editorial boards, I also argue that it represents shifting meanings of anti-colonialism in Cairo - away from more radical rhetoric and international focus towards a more nationalist approach, focusing on development and cultural heritage as part of this anti-colonial platform.

Part of my interest in anti-colonialism is exploring how the emotive meanings shift over this period. To that end, I also utilized Google Vision’s face detection algorithm to try and see if it could detect the ‘emotions’ in the faces in these covers. This approach is not particularly nuanced since the algorithm only detects for joy, sorrow, surprise, and anger and the face detection is far from perfect.

Nonetheless, this graph offer another feature for analyzing the symbolism of these images.

Finally returning that initial image of Nasser, Nehru, and Tito, I have also computed the similarity similarity between this image and all the other covers.

In the future, I hope to use this method to trace how images travel between publications in Cairo, as well as beyond in other Third World coverage of events, which I believe can help us understand the media theory that animated a lot of Third World activism.

So what are my next steps? While these computer vision algorithms are great for initial exploratory analysis, where I’m most interested in pushing further is using the tags and annotations I’ve done of these images as the basis for a supervised machine learning classifier, which can extend my interpretation over a much larger scale of images. I also hope to start bridging my earlier text analysis with these images, calculating how the symbolism in these images supports and diverges from the surrounding text in these magazines and newspapers.

Even though my analysis has some ways to go, there are existing projects that utilize a wide range of methods and utilize a number of other available tools. While computer vision is predominantly a field in computer science department, increasingly digital humanists are exploring the application of digital image analysis to humanities research.

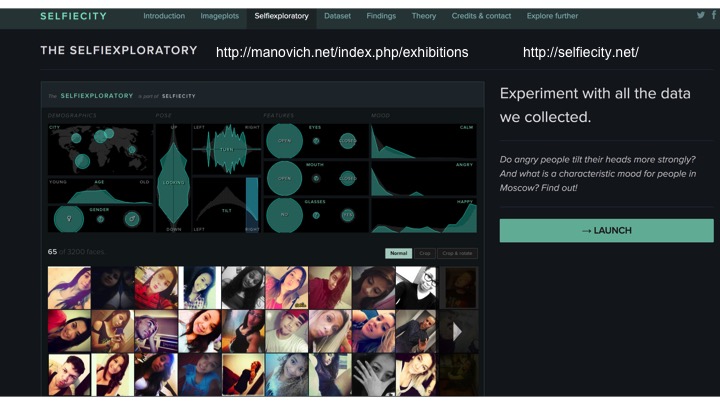

A pioneer has been Lev Manovich and his work with the Cultural Analytics Lab. Some of his more famous work includes the 2009 project “Timeline,” that visualized 4,535 covers of Time magazine (1923-2009), and the project “Selfie City” that explores Instagram selfie trends for different cities. (NOTE: http://selfiecity.net/)

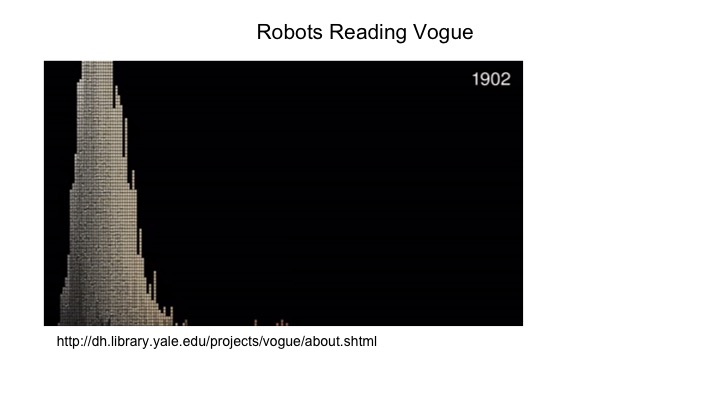

Another large scale project is the Yale Digital Humanities Center’s Robots Reading Vogue created by Peter Leonard and Lindsay King, which allows students and researchers to use 6TB of data to explore Vogue’s 100 year publication history. (NOTE: http://dh.library.yale.edu/projects/vogue/about.shtml)

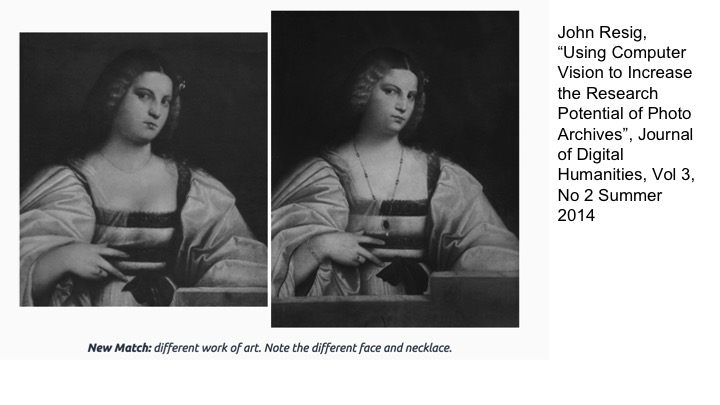

Other great examples include Matthew Lincoln’s study into genre diversity of seventeenth-century Dutch painting and printmaking (NOTE: http://matthewlincoln.net/2016/07/13/dh2016-measuring-genre-diversity-in-seventeenth-century-dutch-painting-and-printmaking.html), Thomas Padilla’s Three Dimensional analysis of the sci-fi magazine IF (NOTE: http://www.thomaspadilla.org/2016/03/02/3dscifi/), and John Resig and Ryan Baumann who have used different tools to analyze image similarity in art museum collections. (NOTE: https://ryanfb.github.io/etc/2015/11/03/finding_near-matches_in_the_rijksmuseum_with_pastec.html & http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/3-2/using-computer-vision-to-increase-the-research-potential-of-photo-archives-by-john-resig/)

As these titles illustrate, much of this research is occurring at the intersection of digital art history and cultural analytics, which makes sense since these researchers are interested in the visual analysis of large datasets. While these projects largely leverage existing datasets, they do provide a great resource for starting to consider the different types of research avenues that digital image analysis can provide.

I would highly recommend looking at these projects if you’re considering trying to use digital image analysis. Digital humanists and social scientists have also been some of the strongest critics of these computer vision and artificial intelligence algorithms and their applications to everything from state surveillance to image searches. Using resources like the Google Vision API in my application raises questions about how ownership of this data, as well as its uses for other algorithms like state surveillance.

Ultimately, computer vision is still a relatively new field, and many of the tools available are not as refined as those for text analysis. Nonetheless, the ability to collect and curate thousands of images is increasingly becoming a reality for historians. For my research, integrating digital image analysis has helped further my exploration into the symbolism of anti-colonialism and opens up the opportunity to explore many new questions. For diplomatic historians interested in public diplomacy, images have already proven to be fertile ground, and I believe integrating digital image analysis into those analyses will enable historians to our hypotheses on a much larger scale. However, I also realize that the barrier to entry is not as easy as some textual analysis tools and understanding the output of computer vision algorithms can be difficult. I hope today I have demonstrated some value for these methods and shown the potential of this newer research method.

If you’re interested, under the hood of this application I’m using a combination of three different computer vision and image analysis libraries that are available in python: Scikit-Image, Pillow, and OpenCV. All of my code is available on Github, and I would be happy to discuss more later.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: